We can't achieve the SDGs without investing in animal health

Marking the United Nations' 75th Anniversary, Harry Bignell, Brooke's Global External Affairs Officer, argues that we cannot achieve the Sustainable Development Goals without investing in animal health systems

This month, the UN is commemorating its 75th Anniversary, putting a focus on all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the month, and holding a special event at the UN General Assembly. Until recently, the world was making slow progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. Now, in light of Covid-19, it is projected that two-thirds of the SDG targets will not be met.

Undeniably, the world in which we now live is a very different place to the one in which the SDGs were first conceptualised. We are facing a global pandemic on an unprecedented scale and have been forced to accept that global pursuit of globalisation, economic growth and expansion has come at a heavy cost. The world is under increasing global stress, including from pandemics, extinctions and environmental degradation.

Discussions at this year's virtual UN High Level Political Forum (HLPF) focused on what this new reality means for the SDGs. Some argued that the goals and their indicators need a radical reconfiguration, while some others argue that we need to step up the implementation of the current goals to safeguard those at greatest risk. A recent article titled 'Reset Sustainable Development Goals for a pandemic world' by Robin Naidoo and Brendan Fisher, argued that the goals and targets must be screened according to three points: Is this a priority post-COVID-19; Is it about development not growth?; and Is it a pathway resilient to global disruptions? The article argues that we must collaborate around a few clear priorities which can be achieved in a less-connected world with a slower economy. In short, opinions differ as to the best way to build back better.

One thing seems consistent, however, and that is insufficient focus on global animal health in these recent discussions. This vital piece of the puzzle is still neglected, despite its evident importance. Covid-19 was passed to humans from animals.

Why focus on animal health systems?

Humans are closer to wildlife than ever before as agricultural and industrial activity encroaches on natural habitats. In the global South, many rural families live in close proximity with livestock that they rely on for their livelihoods. In the global North, companion animals and industrial farming for meat and dairy put humans in daily contact with pets and production animals. Wet markets, illegal wildlife trade and legal trade in animal meat and products - these are just a few examples of where dangerous pathogens can gain a foothold, just like in the case of the coronavirus.

However, this proximity to animals takes place in a context where our animal health systems are not robust enough to protect people from the increased risk disease. 61% of all human infections and 75% of all emerging diseases are zoonotic (transmitted from animals). The World Bank found that zoonotic diseases account for more than 1 billion cases and 1 million deaths per year.

Covid-19 is only one of many zoonotic infections. SARS, MERS, Ebola, swine flu, mad cow disease all came from animal species and had a devastating impact on animal and human populations. And it is not just pandemic outbreaks that we should be concerned about. People are infected with and die from diseases such as rabies, brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis every day.

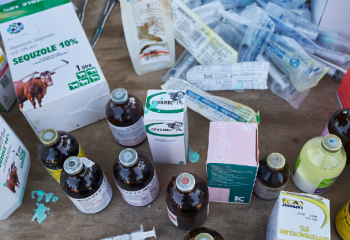

Yet animal health systems continue to be severely underfunded. Inadequate staffing, poor quality or counterfeit medicines, poor organisation of veterinary services and critical shortages in veterinary medicines and vaccines put the lives and wellbeing of millions of people and animals at risk. This needs to change. Our proximity to the animal kingdom and the impact this has on zoonotic pandemics shows a strong case for increased investment in animal health systems.

What does this have to do with the SDGs?

Healthy animals, supported and handled through positive welfare, play a crucial role in achieving the SDGs. Livestock are part of agricultural production and a significant source of animal protein, as well as supporting the livelihoods of millions of people around the world.

Working animals such as horses, donkeys and mules are used in transport of goods and people, including agricultural produce and water, and their work provides a vital revenue to their owners. Animals help feed and clothe people and their work generates income that allows families to pay for education, food, clean water or healthcare.

Healthy animals contribute positively to the achievement of the SDGs, but animals in a state of poor health and welfare not only cannot contribute, but are a significant risk to human health and development.

Our failure to invest in and address the weaknesses in our animal health systems has allowed zoonotic diseases to proliferate, risking the achievement of SDG 3 'healthy lives and wellbeing for all', as well as having a knock-on impact. In short, only once we have reduced the prevalence of communicable and non-communicable diseases, including zoonoses, will we be able to achieve the SDGs.

So, what's next?

We ignore animal health and welfare at our own peril. Development actors must acknowledge the crucial role of animals in the achievement of the SDGs, and include them in their calls for acceleration or reconfiguration and advocating for their inclusion in the targets.

Specifically, we need to rethink SDG 3 'healthy lives and wellbeing for all' to include a One Health approach, which integrates human, animal and environmental health. If viewed in isolation, human health will always be vulnerable.

We need initiatives specifically addressing underinvestment in animal health systems. Brooke has launched a campaign Action for Animal Health which aims to draw together actors to advocate for greater support for animal health systems with a focus on workforce; veterinary medicines and vaccines; animal disease detection, surveillance and management; collaboration for One Health; and community engagement.

Animal health must not be forgotten in discussions about the future of SDGs in these uncertain times. In designing pathways resilient to global disruptions, as suggested by Naidoo and Fisher, we must acknowledge that zoonotic disease is one of such disruptions and investing in animal health is part of the solution.

The evidence is clear: we cannot achieve the SDGs without investment in animal health.

References

- 21 September 2020 by Brooke: https://www.thebrooke.org/news/we-cant-achieve-sdgs-without-investing-animal-health (Brooke is an international charity that protects and improves the lives of horses, donkeys and mules which give people in the developing world the opportunity to work their way out of poverty.)