Infonet-Biovision promotes the IFOAM Principles for animal health and welfare management as they contain guidelines for humane treatment of livestock.

In the following we present the key features of the standard system with focus on animal husbandry (health and welfare, medicine, feeding, breeding)

The IFOAM Basic Standards on Organic Farming

The International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) produced a set of international organic standards.

The standards give guidelines on organic farming.

The international standards are used by countries to develop their own standards, which take into account different farming systems. Many countries have organic standards authority which develops national standards and awards accreditation symbol to farms that apply the standards. This symbol then allows farmers to market certified organic produce and consumers to identify and buy organic produce.

What is organic agriculture?

-

IFOAM defines organic agriculture as a production system that sustains the health of soils, animals, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects.

Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved.

NB Organic farming is based on a number of objectives and principles designed to minimise the negative human impact on the environment, while ensuring the agricultural systems operate as naturally as possible. Furthermore, organic farming is also part of a larger supply chain, which encompasses food processing, distribution and retailing sectors (Lampkin, 1990; IFOAM, 2006)

What products are covered by the Standard System?

The IFOAM norms cover a wide range of products including crop production, livestock, wild products, processing, fiber processing, and aquaculture among others.

Typical organic farming practices include:

- Strict limits on chemical synthetic pesticide herbicide and synthetic fertiliser use, livestock antibiotics and hormones, food additives and processing aids and other inputs.

- Absolute prohibition of the use of genetically modified organisms.

- Wide crop rotation as a prerequisite for an efficient use of on-site resources.

- Taking advantage of on-site resources, such as livestock manure for fertiliser or feed produced on the farm.

- Choosing plant and animal species that are resistant to diseases and adapted to local conditions.

- Raising livestock in free-range, open-air systems and providing them with organic feed.

- Using animal husbandry practices appropriate to different livestock species and humane treatment of animals

|

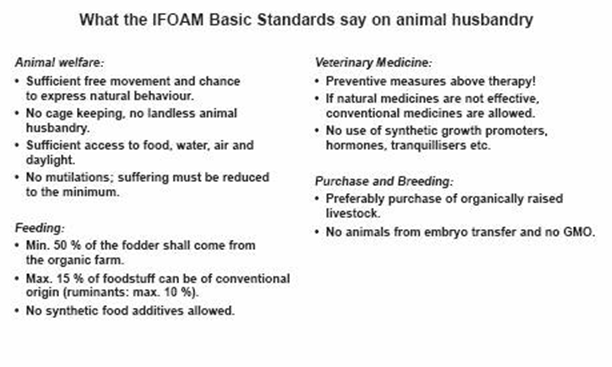

IFOAM basic standards on animal husbandry There is a range of standards regulating the management, shedding, feeding, veterinary treatment, breeding, purchase, transport, and slaughter of farm animals. Some of the most important standard requirements are listed in table 1 Below. NB: Organic animal husbandry is not limited to to use of organic feeds and avoiding synthetic food additives, but also includes satisfying the various needs of farm animals like good health and welfare, these include minimizing . suffering due to mutilations, improper tethering or isolation. For various reasons, landless animal husbandry (i.e. fodder purchased from outside the farm, no grazing land) is not permitted in organic farming. |

Requirements:

The farmer shall ensure that the environment, the facilities, stocking density and flock/herd size provides for the behavioral needs of the animals.

In particular, the farmer shall ensure the following animal welfare conditions:

- Sufficient free movement and opportunity to expres normal patterns of behaviour, such as space to stand naturally, lie down easily, move around freely, groom themselves, sleep and nest comfortably in a dry place, assume all natural postures and movements such as stretching, scratching, perching, running and playing.

- Sufficient fresh air, water, feed, thermal comfort and natural daylight.

- Access to resting areas, shelter and protection from sunlight, temperature, rain, mud and wind adequate to reduce animal stress

- Provision of suitable materials and areas for exploratory and foraging behaviours

- Herd animals shall not be kept in isolation from other animals of the same species. This provision does not apply to small herds of mostly self-sufficient production. A farmer may isolate male animals, sick animals and those about to give birth.

- Do not use construction materials, methods and production equipment that might harm the animals.

- Farmers shall manage pests and diseases in livestock housing

NB In addition to these general welfare conditions for all animal categories, provisions for specific animal groups should be taken into account, for example:-

- For cattle: social grooming and grazing

- For pigs: rooting, separate lying-, activity/dunging- and feeding-areas, free farrowing, group housing

- For poultry: nesting, wing stretching/flapping, foraging, dustbathing, perching and preening

Read more on IFOAM Standards

|

|

What are the FOUR principles of Organic Agriculture?

1. The principle of health 2. The principle of ecology 3. The principle of fairness 4. The principle of care

In the section about Human-animal relations, you can also find the IFOAM principles specifically guiding the relations which we as humans can create with animals. |

1. Principle of health

Organic Agriculture should sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal, human and planet as one and indivisible.

- The health of individuals and communities cannot be separated from the health of ecosystems - healthy soils produce healthy crops that foster the health of animals and people. Health is the wholeness and integrity of living systems.

- Health is not simply the absence of illness. It is the maintenance of physical, mental, social and ecological well-being. Immunity, resilience and ability to regenerate are key characteristics of health.

- The role of organic agriculture, whether in farming, processing, distribution, or consumption, is to sustain and enhance the health of ecosystems and organisms on all levels.

- In organic agriculture, health and welfare of the animals should be promoted at all levels, and animals should never be placed under conditions which can cause illness.

|

2. Principle of ecology Organic Agriculture should be based on living ecological systems and cycles, work with them, emulate them and help sustain them.

|

3. Principle of fairness

Organic Agriculture should build on relationships that ensure fairness with regard to the common environment and life opportunities

- Fairness is characterized by equity, respect, justice and stewardship of the shared world, both among people and in their relations to other living beings.

4. Principle of care

- This principle states that precaution and responsibility are the key concerns in management, development and technology choices in organic agriculture.

- Organic Agriculture should be managed in a precautionary and responsible manner to protect the health and well-being of current and future generations and the environment.

- Given the inadequate understanding of ecosystems and agriculture, care must be taken.

- Intervene whenever necessary, if something is wrong or risky for the animals, but do not intervene when things are fine.

IFOAM Standards on Mutilations

What are mutilations?

Mutilations are all forms of physical injuries done to the living body, which degrades the appearance or functions, and which have no healing purpose.

In livestock farming, animals are most often subjected to mutilations because it decreases injuries to each other .

Are mutilations allowed in organic agriculture?

Mutilations are generally not allowed in organic animal farming.

.

This means that animals should be intact, and their integrity should be kept.

The IFOAM basic standards give the following recommendations:

- Farmers should select species and breeds that do not require mutilations

- Exceptions for mutilations should only be made when suffering can be kept to a minimum

- Surgical treatments should only be used for reasons of safety, mitigation of suffering and the health and welfare of the livestock.

The first recommendation stresses that injuries among animals should be prevented by selecting animals with minimum risks. For example, some sheep have loose and folded skin, hence high risk of attacks from flies and maggot infestation. These sheep are subjected to a practice where their skin is cut so that it is less folded – this is called ‘mulesing’. This should be avoided in organic farming.

- Castration

- Tail docking of lambs

- Dehorning

- Ringing

In research and practice, solutions are constantly searched for to avoid mutilations, including the above mentioned.

How can we judge whether a mutilation is severe or less severe?

A mutilation is always severe, because of the physical injuries it inflicts on the animals. But some are very severe, because they have long lasting impact on the animal. Guiding Questions

- Is the animal welfare or integrity affected permanently?

If the answer yes, then it is a severe mutilation. Castrations fall into this category.

Beak trimming of poultry can lead to permanent pain when pecking for feed on the ground, and are as such a severe mutilation, because searching for feed is a profound part of poultry’s normal behavior.

Dehorning or disbudding of cattle can change the power relations in a herd of cows, but they still form a hierarchy, so this is not regarded as very severe by some people , but by others as severe because it changes the cow’s ‘zone of tolerance’, that is, the zone which she will accept others before a confrontation. This makes it possible for humans to keep more cows in smaller space.

- Is the mutilation necessary for animal related purposes? Does the animal profit from it?

A caesarian can be regarded as a mutilation which the animal benefits from. If it is necessary for the survival of its offspring. Most caesarians are result of a ‘normal animal’ having difficulties in giving birth in a case. There are some breeds which are very likely to require a caesarian when giving birth; they should be avoided in organic farming because it is fair to avoid mutilations when something can be prevented through the choice of breed or farming system. We always have to ask ourselves whether the mutilation can be avoided by removing any underlying cause?

- Is the mutilation necessary to meet some human related aims?

As stated above, most mutilations are regarded as ‘necessary’ for human use purposes. The question is whether we can avoid those mutilations by meeting the needs of animals? One example is in pigs. Pigs will attack each other if they are frustrated and are not sufficiently stimulated, and e.g. bite in each other’s tails. This could be prevented by giving them conditions that minimize such triggers for example space and opportunities to root in some material.

But, some farmers solve this vice it by cutting the tail in a young age.

- What will happen if the mutilation is not done? Which alternatives do we have?

For example, if avoiding castration, the consequence could be that male animals cannot be kept in a group without constantly fighting, or mating with their close relatives among the females. Alternative housing conditions. can be considered. But when it is ‘normal practice’, a complete change of farm design can be considered.

What is accepted by society?

This is really not a criteria for accepting or rejecting a mutilation. It is here to provoke our thought process on what is perceived as “normal” by the society and compare it with the above criteria.

Different types of mutilations

Below a list of different types of mutilations, most of which are prohibited in organic farming. Alternatives are discussed.

- Beak trimming

- Beak trimming (sometimes referred to as beak treatment) is a mutilation that involves removal of e part of the upper and lower beak . Beak trimming is applied to avoid excessive pecking behavior. Pecking is a natural poultry behavior

- In commercial poultry keeping; beat trimming it can result in feather pecking and cannibalism, which cause lot of damage/pain to a bird and can lead to high mortality. Not only laying hens and layer and broiler parents are beak trimmed but also turkeys (the upper beak). The trimming is normally done using a hot blade or with infrared device. Beak trimming is done on poultry that are young as one day up to 5 weeks of age.

- This cause pain and stress and has a long term influences the behavior

- Bea severely affects the anatomy of the animals and should not be used in organic farming.

- Castration

- Castration is the removal of testicles from male animals (stallions, boars, bucks, rams). It is done to reduce inbreeding and to improve fat distribution in beef animals.

- In pigs it is done to preventboar taint. In Stallions it is done to to enable easier handling

- Castration is painful and causes stress and influences the behavior severely, because castrated males cannot show sexual behavior. The least painful method is recommended in organic production systems.

- Castration is commonly practiced in organic farming, but research is ongoing to find alternatives because it severely affects the animal’s sexual behavior.

- Despurring

- Despurring is stopping the growth of the spurs of cockerels immediately after hatching by pushing the spurs against a hot iron. The process of despurring causes pain and stress.

- Despurring is done to avoid injuries during mating. Despurring is not explicitly mentioned as accepted in the IFOAM norms.

- Dubbing

- Dubbing is the cutting part of the combs of cockerels with a small scissor to prevent combs from growing.

- When cockerels have too large combs there vision is limited resulting in lower fertility. This is unacceptable in organic farming, and can be solved by choosing the right breeds.

- Disbudding.

- Disbudding is the destruction of horn forming cells in cattle, goats and sheep at a young age. It is done using a hot iron or caustic powder placed on the horn bud to stop it from growing.

- In some countries disbudding is allowed in organic farming. A local anesthetic must be used to prevent suffering.

- Dehorning

- Dehorning is that removal of horns from cattle, goat and sheep at an older age by cutting or sawing them. It can be allowed inorganic animal husbandry only if animal suffering is minimized and anesthetics are used.

- Mulesing

- Mulesing is the removal of part of the skin of the hind part of sheep to prevent it from having parasites and maggots under the skin. It is completely forbidden in organicfaerming.

- Breeds which are prone to this should be avoided in organic farming.

- Nose ringing. Nose ringing is done to have better control over bulls and boars but also to prevent animals from cross suckling. In some places it is forbidden to transport bulls unless they are nose ringed. It is painful when applied and it changes behavior. E.g. some nose ringed sows will graze instead of rooting.

- It can be allowed in organic farming only if animal suffering is minimized and anesthetics are used.

- Pinioning

- One or both wings are sometimes cut to prevent poultry from flying. This can be a very painful practice and should be avoided if it involves touching nerves, or causing bleeding. It can sometimes be done by just cutting tips or parts of the feathers, without bleeding.

- Removal of extra teats

- Is the surgical removal of extra teats. This should be done at 2 to 3 weeks of age.

- Tail docking

- Tail docking is amputating (part of) the tail of in sheep and pigs, and dogs .

- It is done to avoid parasite attack in sheep, cannibalism in pigs and for “beauty”in dogd

- It is painful and stressful experience and it influences behavior . In organic lambs it is allowed when animal suffering is minimized and anesthetics are used. In all other cases it is forbidden.

- Toe clipping

- This refers to clipping of toes of breeder cockerels. It is normally done using a hot blade or wire immediately after hatching.

- It is painful and causes stress and it could causes pain. The mutilation is done to prevent injuries to the hens during mating.

Mutilations for identification and record keeping

- Brand marking for identification

- For record keeping, it is practical to mark animals just after birth. As discussed in the section of record keeping identification can be done by having certain characteristics, such as color patterns or hair whorls registered.

- Colored number or stripe on the skin,- is mostly temporary and has to be repeated. Collars or bands around the feet can fall off. For these reasons, permanent identification methods are used. Ear tagging, tattooing and branding can be used.

- Ear Clipping

- It is common practice for donkey owners, particular in rural areas and where donkeys live in large herds, to mark their animals.

- This is often done by cutting patterns in their ears or the whole ear.

- This method of brand marking should be avoided.

- Ear notching

- Ear notching is putting a mark in the ear of animals with a pin through a hole in the ear.

- Freeze branding

- Freeze branding is marking animals on the skin with an iron, cooled down in fluent nitrogen (-85oC). It causes stress while performed and pain because the pigment in the skin is destroyed. It recovers after a few days and does not cause pain for long

- Hot branding

- Hot branding is putting a number or other mark with a hot iron on the skin of animals.

- It is is extremely painful, but it does not cause chronic pain.

- Tattooing. Tattooing is making a wound where ink is applied, into animals skin of the ears, lips or tongue to create a pattern.

Review process

- Dr. Mette Vaarst, veterinarian, and Gidi Smolders, agronomist, orgANIMprove

- Muhammad Kiggundu, Makerere University

- Aage Dissing

- Inge Lis Dissing

- Monique Hunziker

Information Source Links

- IFOAM Norms and Standards, 2014. Full title: 'The IFOAM Norms for Organic Production and Processing, Version 2014.

- IFOAM Training Manual for Organic Agriculture in the Tropics http://shop.ifoam.org

- IFOAM, 2009. Definition of Organic Agriculture. IFOAM, Bonn, Germany

- Lampkin, N., 1990. Organic Farming. Farming Press, Ipswich

- Research Institute of Organic Agriculture, Fibl, Switzerland. http://www.systems-comparison.fibl.org

- Willer, H., Kilcher, L. (Eds.), 2010/2011. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2010. IFOAM/FiBL, Bonn, Germany and Frick, Switzerland. http://www.organic-world.net