Tick borne diseases: Anaplasmosis

Local names: Embu: ndigania / Gabbra: biraa / Kamba: nthiana / Meru: nthiana / Kipsigis: cheptikonit / Gikuyu: ndigana / Maasai: Entorhobo, lipis, endigana, engemomywa oldigana oiboir / Samburu: mporot, ndiss / Somali: ndaratu, gabgab, jooge, racamo / Swahili:ndigana baridi / Turkana: lonyang', lopid / Nandi: kipkuit /

Common names: gall sickness, anaplas, anaplasmose bovine (French)

Description: Tick borne disease

Introduction

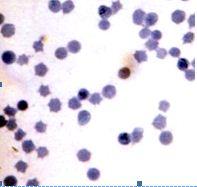

Anaplasmosis an acute (rapid onset and short but severe), fever producing disease of cattle, usually transmitted by Boophilus species Blue ticks and caused by a parasite which multiplies by binary fission in red blood cells, causing severe anaemia. Severe Anaplasmosis is caused by Anaplasma marginale. This parasite occurs at the edge of the red cells. A mild, usually inapparent form is caused by Anaplasma centrale. This parasite occurs at the centre of the red blood cell.

The incubation period of the disease is about 2 - 12 weeks and is directly related to the infective dose. The disease occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Mode of spread

Anaplasmosis is not contagious. The source of infection is always the blood of an infected animal. Transmission does not take place by contact but generally via the medium such as the:

Blue tick: This is a one-host tick, spending its entire life on its host and for whose control once-weekly dipping or spraying is generally appropriate.

|

Blue tick (Boophilus sp) (c) Dr. John W. McGarry, School of Vet Science in Liverpool

|

Biting flies, contaminated instruments such as injection needles, oxpecker birds can also transmit infecton.

Wild animals and other domestic animals can be infected and become reservoirs of infection

Infections in the sucking young usually does not happen. Once infected, animals remain carriers for life. In areas where cattle first become infected with Anaplasma marginale early in life, losses due to anaplasmosis are minimal. In animals less than 1 year old Anaplasmosis is usually subclinical, that is, there are no symptoms. in yearlings and 2-year-olds it is moderately severe, and in older cattle it is severe and often fatal.

Exposure of calves to infected ticks gives them an often life-long resistance. Paradoxically efficient tick control at this stage of their life will later expose cattle to possible life-threatening anaplasmosis. These facts must be kept in mind at all times.

Zebu cattle, with their relative resistance to heavy tick infestations, are less likely to be infected, but they are just as susceptible as European breeds. Carrier animals serve as reservoirs for further transmissions.

Serious losses can occur when mature cattle with no previous exposure are moved into areas where the disease is prevalent or when transmission rates are insufficient to ensure that all cattle are infected before reaching the more susceptible adult age. This latter situation can occur when a previously effective acaricide becomes ineffective, especially when it has previously been effective from calfhood into adulthood.

Clinical signs and diagnosis

Onset of illness is characterised by a:

- rising fever of up to 41 degrees Celsius (106 degrees Fahrenheit),

- drop in milk production, and

- decreased appetite. Severely affected animals lose condition rapidly and very severely affected animals may die within a few hours of the onset of symptoms.

- severely affected animals are depressed, lose their co-ordination and become breathless and lag behind the rest of the herd if exerted. If forced to walk some of these animals may even lie down. These symptoms are directly related to the degree of anaemia caused by the destruction of red blood cells.

- examination of the eyes and vulva will reveal a change from a healthy pink to a pale white to yellow, or even light orange colour. This indicates the onset of jaundice due to liver damage. The teats of a milking animal appear pale or white in colour.

- there is a rapid, pounding heart rate. This is easily heard by pressing one's ear against the animal's pelvis. This loud beat, heard several feet from the heart itself, is almost diagnostic for Anaplasmosis. It cannot be heard in a normal animal.

- the urine may be yellow or even brown, but, unlike Babesiosis (Redwater) contains no red blood cells.

- constipation is common.

- pregnant animals often abort.

- some animals are hyperexitable and aggressive, charging and attacking people.

- in the severe form of the disease, there may be death if immediate treatment is not given.

- in dead animals, blood is thin and watery and the flesh is pale yellow. The liver is yellowish orange. The gall bladder is large and full of brownish greenish fluid and the kidney is large and soft. The spleen is enlarged and mushy.

Diagnosis

A presumptive diagnosis can be made based on an assessment of the history, clinical and post mortem signs, together with the appearace of ticks and an anaemia without red blood cells in the urine. A peripheral blood smear from the ear should be taken for laboratory analysis by qualified personnel to confirm the disease.

Anaplasmosis is generally not such a severe disease as Babesiosis (Redwater), with which it might be confused. In Babesiosis the urine contains red blood cells, sometimes is almost black in colour and the individual death rate is usually much higher.

Prevention and recommended treatments

Prevention and control

- Regular dipping and spraying with effective solutions to control tick infestations are vital preventive measures. In non-East Coast Fever areas, and in most extensive systems, young calves are often not dipped for the first few months. This allows them to contract the disease and confers immunity.

- Eradication is generally not practicable due to the ubiquity of the carrier ticks, the long period of infectivity in carrier animals, the presence of carriers in the wild animal population and the difficulty of identifying infected animals.

- Vaccines are available and used in some countries. These are either livng attenuated strains of A. Marginale coupled with treatment if required, or the less pathogenic A.Centrale. Severe reactions can occur with both types of vaccine.

Recommended treatment

- The drugs of choice for treatment are tetracyclines and Imizol (midocarb dipropionate)

- Oxytetracycline long-acting solution is effective given early in the disease at a rate of 30mg per kg i/m. Likewise imidocarb at 3mg/kg. These dosages will not elimiate the carrier state. For this repeated injections at a higher dose level are required, which may not be appropriate in Kenya at the present, due to the widespread abundance of the organism in recovered, immune animals.

- Constipated cattle should be given a dose of Epsom Salts - 500g (1lb) is a suitable dose for an adult animal. Also molasses drench is useful combined with plenty of drinking water. Careful nursing and provision of an appropriate diet with green feed will assist recovery. Avoid giving hay, dry straw and grains to constipated cattle.

Babesiosis (Redwater)

Local names: Luo: aremo / Kiswahili: ugonjwa wa kukojoa damu / Turkana: eyiala, lopid, lobul / Nandi: sasioto / Kipsigis: beek che biriren / Gikuyu: munyuria / Maasai: enado nkulak, ol odulak / Meru: maumago yamatune / Samburu: nkula, ngula / Borana: dukub shilmil / Pokot: Kipirir, pkison

Common names: Piroplasmosis, Red Water, Tick Fever, Texas fever, La tristeza, Piroplasmose bovine (French), Fiebre del texas (Spanish)

Description: Tick borne disease

|

|

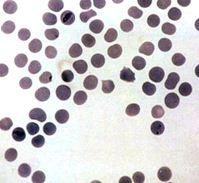

| B.Bovis | B.Bigemia |

|

© USDA

|

© USDA |

Introduction

Babesiosis or Redwater is a very severe disease, considerably more so than Anaplasmosis.This is a fever producing disease of cattle, caused in Africa by the protozoan parasites Babesia bigemina and Babesia bovis. The disease occurs worldwide but has serious implications in the tropics because of the high prevalence of the host ticks. Other names of this disease are Red water and Cattle tick fever.

Mode of spread

Babesiosis parasites are spread only through their carrier tick. Ticks acquire babesia infections from infected animals.

In Africa, the Cattle tick which transmits B. bovis was introduced at the end of the 19th century. B.bovis thus only occurs in those areas of Africa to which Cattle tick has spread. In Kenya the Blue tick, Boophilusdecoloratus, which is the main transmitter, can only transmit B. Bigemina and as a result this species assumes more importance than B. bovis.

Tranmission occurs transovarially, that is, from the maternal body to eggs within the ovaries. In areas where Babesiosis occurs,two features are important in determining the risk of the disease occuring.

- Calves have a degree of immunity (related both to colostral-derived antibodies and to age) that persists for about 6 months.

- Animals that recover from Babesia infections are generally immune for life.

Thus, where there are high levels of tick infestation, all newborn calves will be infected by Babesia parasites by 6 months of age. On recovery from initial infection they are immune but harbour the parasite (premune) and may remain carriers for up to 2 years. In areas where Babesiosis is prevalent, constant reinfection ensures that such cattle remain carriers permanently, although the premunity may break down due to other factors such as stress or other diseases occuring at the same time, resulting in clinical babesiosis.

This stability can be upset by either natural factors such as seasonal variation or artificial factors such as drought, dipping etc. Reduction in tick numbers to levels such that tick transmission of Babesia to calves is insufficient to ensure all are infected during this early critial period. In this case some animals remain at risk. If these are infected as adults, they may suffer severe clinical reactions.

Thus in enzootic areas:

1) Enzootic stablity:- The continuous presence of Babesia in both cattle and ticks with frequent acquisition of the parasite from active infective ticks ensures that cattle are infected in calfhood and remain carriers due to contant reinfection.Under these conditions clinical babesiosis is minimal.

2) Enzootic instability:-The infection of Babesia is such that not all cattle are infected as calves, and therefore some animals remain susceptible. If these are infected as adults, they may suffer severe clinical reactions. Such conditions arise when the number of ticks fluctuate due to factors such as seasonal variation, drought, dipping etc.

The incubation period ( the time from tick attachment to the appearance of parasites in the red blood cells) is normally in the range of:

- 8-16 days for B.bovis as transmission occurs early larval stages of ticks

- at least 9 days longer for B.bigemnia because infection is not transmitted until the nymph and adult stages of the tick begin to feed.

Ticks acquire babesia infection from infected animals.

Signs of Babesiosis

Babesiosis or Redwater is a very severe disease often confused with but more severe than Anaplasmosis.The first indication that the disease is present may be finding of a dead animal - usually an adult - in the paddock.

The parasites invades the red blood cells where they multiply and break out to invade more red blood cells. The released parasite and host constituents from the destroyed red cells are toxic, resulting in shock, anaemia and short supply of oxygen to tissue.

- Blood in urine: The release of haemoglobin results in jaundice and blood in the urine. The urine is usually, but not always, red in colour. Sometimes the urine is dark red and sometimes it can be almost black. Such animals are very ill indeed and usually die.

- High temperature: There is a rise in temperature. This is often 41 degrees Celsius (106 degrees Fahrenheit) or higher.

- Affected animals become depressed, listless, rumination ceases, milk yield drops, and they refuse to eat.

- Pregnant animals often abort

- Pale eyes and gums: The eyes and gums are pale from anaemia and jaundiced (yellowish), due to bile pigments in the blood stream.

- In severe cases, brain capillaries become blocked with infected red blood cells causing cererbal babesiosis resulting in incoordination followed by posterior paralysis,or by mania,convulsions and coma. Such animals rarely recover, despite treatment.

- In less severe cases of the disease, infected cattle have fever lasting about 1 week and remain sick for 3 weeks. This group of animals may recover slowly while pregnant animals may abort. Recovered animals remain permanent carriers of the disease. Zebu cattle appear to have more resistance to babesiosis than do European breeds.

- Post mortem fndings reveal an enlarged spleen, a swollen liver, with an enlarged gall bladder containing dark green granular bile, congested dark-coloured kidneys, and generalised anaemia and jaundice. The urine is usually, but not always, red in color.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be confirmed in a laboratory by the examination of a stained blood smear taken from the ear or tail tip. A number of serological tests are available but generally these are out of reach under local conditions. Under the microscope B. bigemina parasites are large organisms, seen within the red cells in pairs at an acute angle to each other. B. bovis are small and lie at an obtuse angle to each other.

A number of serological tests are available such as the indirect fluorescent antibody test, ELISA and the complement fixation test, but generally these are out of reach under local conditions.

Other diseases must be considered when an animal is seen to be passing red urine. Possibly the most important of these is:

- Leptospirosis. This disease also presents with red urine, jaundice, abortion, depression and loss of appetite. However there are no blood cells in the urine, it affects all ages, including young calves and the degree of jaundice is often more profound due to the more chronic nature of the disease. Sensitivity to light of white skin is common. Leptospirosis often occurs during periods of heavy rain as rodents frequently are carriers, passing the infection in their urine, which can then survive for extended periods of time in pools of water.

- Heartwater may also initially be confused with cerebral babesiosis but there are clinical differences and no babesia parasites will be found in stained smears.

- Anaplasmosis is a less severe disease with no blood cells in the urine.

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Prevention and Control

At the moment in Kenya prevention must rely on tick control and trying to reach a situation of enzootic stablity by aiming to control the ticks but not the disesase they transmit so that young stock are infected and develop a lifelong immunity. This can be difficult in areas where other ticks transmitting other diseases such as East Coast Fever occur. The Blue tick is normally the first tick to develop resistance to new acaricides. The results of this resistance can be dangerous.

It is advisable to keep suitable breeds of animals in areas where the disease is prevalent. Such breeds may include indigenous cattle and their crosses with exotic cattle. With these breeds the dipping or spraying intervals can be extended as these local breeds have more resistance to babesiosis and also to ticks, but with European breeds, tick protection is required.

The whole picture must be considered before taking any decision regarding extension or reduction of dipping or spraying intervals.

Vaccination using live, attenuated strains of the parasite has been used successfully in a number of countries. Combined vaccinaton and strict control of ticks is an effective control strategy when exotic cattle are introduced. Young animals can be vaccinated with live vaccines to counter periods of inactivity of ticks. These techniques are currently unavailable in Kenya so a carefully monitored tick control program is required to allow the development of resistance in conjunction with the control of other tick-borne infections.

Recommended treatment

Two drugs are currently available for the treatment of Babesiois. These are:

- Diminazene aceturate (Norotryp, Berenil etc) and

- Imidocarb dipropionate ( Imizol).

Dimiazene is given at a dose rate of 2 to 5 mg/kg by intramuscular injection.

Imidocarb is given at a rate of 1.2 mg/kg by subcutaneous injection.

Higher doses of both drugs will protect animals for several weeks.

Large species of Babesia such as Bigemina are more responsive to treatment than the small species such as Bovis which may require a larger dose of the same drug to effect a cure. Fortunately Bigemina is the more common species in Kenya.

The aim of treatment is to promote recovery from the clinical disease while allowing some organisms to persist in order to allow the animal to develop an immunity to the disease. Too rapid a cure can result in the animal being susceptible to reinfection.Thus, treatment which immediately sterilizes the infection should, if possible,be avoided. This can be difficult when faced with severe cases when delayed treatment means death of the animal. In such cases, preventive treatment of the rest of herd should be considered.

Supportive treatment is advisable. This may include the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, multivitamins, fluid replacement and in some cases, blood transfusions.