Introduction: Management of catchment areas

|

The water available to a farming system is firstly determined by the ratio of precipitation and evaporation (including transpiration) of water. When rainfall exceeds evaporation and transpiration (ET), there is generally enough water available for plants to grow. When rainfall is less than ET, water availability for crops decreases. How much rainfall can actually be used by the crops is also determined by the characteristics of the soil, the depth of rooting of the crop and the management of soil and water.

Water management does not only include the analysis and planning of water availability for households and agriculture, but has also to take other aspects into account such as soil protection and community interests. Thus, management of catchment areas integrates water management, soil protection, as well as health and socio-economic topics into a process, ideally leading to a sustainable and economically viable environment that can generate sufficient household income.

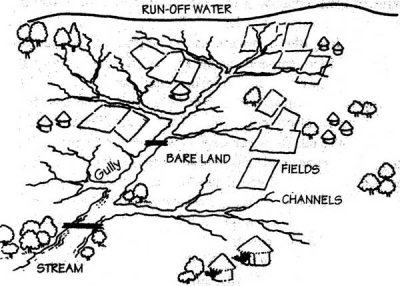

Definitions and principles A catchment area (in America also called watershed) is defined as any surface area from which all rainwater is drained into the same watercourse. Small streams merge to larger streams, continuously growing to a river or ending in a lake or the sea. The catchment area resembles a tree, where leaves lead to small branches and these small branches lead to larger branches and so on, eventually reaching the trunk of the tree. Watersheds have both biophysical and socio-economic characteristics, i.e. climate, drainage and water, soil, vegetation, topography as well as population, farming systems, social setups, economic activities, vulnerability profile, gender, etc.

|

|

1) Participatory

The communities of the selected catchment area need to be involved in all stages of the watershed development process, i.e. planning, implementation, and management.

2) Gender sensitive

Women are the main sufferers if water management is uncoordinated, since they have to gather the water for household use. They are the key to ensuring the practicality and sustainability of the process.

3) Build on local experience and strengths

Local knowledge is essential to improve existing technologies and adapt new ones. Best practices should be identified and disseminated.

4) Realistic, integrated, productive, and manageable

Watershed development planning should be realistic and build on local capacity and locally available resources. Integrated management of the local natural resources and optimal use of social resources are essential parts of watershed development. Production and conservation aspects should be included, so households quickly receive benefits from their engagement.

5) Watershed logic and potential respected

The watershed development activities have to follow the logic of the watershed. Simple descriptions of land use and main features can help to adapt plans to the local conditions.

6) Flexibility at different levels

Flexibility and adaptability are needed for pragmatic implementation and management of a watershed development plan.

7) Cost-sharing and empowerment/ownership building

Cost-sharing by stakeholders contributes to the sustainability of a project. Also other forms of local contributions are possible, such as labour and local materials.

8) Complementary to food security and rural development mainstream

Additional elements such as basic services and social infrastructures can be integrated in watershed planning.

Watershed size

1) most parts of a community comprising the smallest unit available;

2) more than one community where the interactions between two or more communities are closely linked to the watershed they share;

3) only a portion of a community that is widely scattered having more than one main watershed within the community.

Degradation of catchment areas

Potentials: Optimized use of water and soil in a catchment area

Water harvesting opportunities

Sustainable source of safe drinking water

Land rehabilitation, reclamation and productivity enhancement

Protection, development and sustainable management of forests

Sustained, long lasting and effective use of rural infrastructure

Promotion of income generation activities

Catchment area development and conflict resolution

Community involvement - The entrepreneurial approach

Entrepreneurial approach

One approach, namely the entrepreneurial approach, has succeeded very well and it is highly recommended as a model for future development of rural water and sanitation schemes. This new approach to community participation was successfully tested by the Danida/Government of Kenya funded Water Pilot Project in Kitui and Taita Taveta Districts, whereby 68,000 people in the most arid parts got piped water within 2 km from their homesteads from 2004 to 2006. Detailed information is presented in a manual: Water for Rural Communities (2006), which can be read on www.waterforaridland.com.

By this entrepreneurial approach, the communities were paid cash for 50% of the cost of their labour and locally available materials, while the other 50% was recorded as the community contribution to the construction costs. This improved the living standards and economic development of the individual households as well as for all the communities involved in the 6 water projects.In other words, the main difference between this entrepreneurial approach and the more conventional strategy for community participation is that the people involved in the construction activities are being paid for their work, instead of paying for having the work done by others.

In conventional develop programmes local labour resources are most often planned and used for what is termed as community participation activities but in reality is free labour for government agencies and contractors. Using the available local human capital in such a narrow way has proved to be far too limited and has neither achieved ownership by the community nor sustainability of water supply schemes.

In the entrepreneurial approach, both men and women are seen as a development resource and treated as such through appropriate training on skills which give opportunities for employment. The entrepreneurial methodology could be applied throughout the poor and rural areas of the world thereby create employment for millions of idle and left-out youths who could construct simple but much needed water sources such as subsurface dams built of soil in otherwise dry riverbeds, contour trenches and terraces on farm land and tree planting.

Main Contractor's assignments

The entrepreneurial approach for the 6 water and sanitation projects was implemented by

1) a Consultant who was contracted as the Main Contractor (MC) by Danida and

2) the Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MoWI) to produce the implementation strategy for the projects.

The MC's assignments consisted of the following activities:

Training programmes

Training of Project Committees

When the Project Document was approved by the relevant ministries, the training of communities was initiated by the District Commissioner (DC) and the Main Contractor (MC) who invited each of the 6 communities for a public meeting in their project areas.

During these meetings the Project Document was presented, explained, discussed and agreed upon by the communities in the local vernacular as well as in English. Each of the 6 communities was encouraged to elect a Project Committee consisting of an equal number of men and women before the next meeting would take place.

Training on legal matters

At the second round of meetings, each of the 6 Project Committees was invited for one week's training on legal matters and construction procedures at a training centre. Two Community Trainers conversant with the local vernacular trained the 6 Project Committees in legal matters such as registration with Social Development and the Water Services Board, By-laws, Land Agreements, membership fees and penalties.

The contracts allowed for 50% cash payments to the communities for their delivery of labour and construction materials, while the other unpaid 50% was regarded as their contribution towards cost-sharing of the construction costs of their water projects. When an Implementation Contract was signed between the Project Committees and the MC, the construction work was started.

The main objective of training the communities is to ensure that there is capacity within the community for operation and maintenance of the water projects. Other objectives are creating income for the communities, while reducing construction costs.

Training of subcontractors

Store keepers. The first activity was to train the 25 young women as Store-keepers for hardware materials and procurement of water, sand, crushed stones (ballast), hardcore stones and other locally available construction materials.

Field assistants. Secondly, the project committees motivated the elderly and less mobile community members to collect stones and crush some of them into heaps along roads where it could be measured in wheelbarrows and loaded onto hired tractors with trailers, while the Storekeepers would pay cash according to the number of wheelbarrows loaded. More mobile community members would load the tractor trailers with water or sand from riverbeds and deliver it to the construction sites.

Builders. Thirdly, 50 experienced builders were contracted as subcontractors to build the various parts of the 6 water projects, which consisted of sinking 3 well intakes and drilling 2 boreholes into riverbanks, laying 2 infiltration galleries and building a subsurface dam and a weir in riverbeds, constructing 4 pump houses with electric pumps powered by diesel generators, construction of 3 spring intakes, 23 water tanks and 81 water kiosks or tap stands, excavation of 157 km of trenches for pipes, laying of pipes with wash-out and air valve chambers in the trenches.

Trainers for local builders. Fourthly, the 50 subcontractors, who also functioned as trainers for the local builders, hired some 400 men and women in equal numbers and as recommended by the Project Committees to assist them in the construction work as trainees under the supervision of the Design Engineers and Ministry staff.

Assistant manager. Fifthly, trained an Assistant Manager to assist with managing a Danida grant of Ksh 129.4 million (US$ 1.85 million) for the projects and with overseeing the fieldwork during the 18 months of implementation.

Water User Association

The second training course also assisted the project committees to change their project into a Water User Association (WUA) to be registered as a Water Supply Provider (WSP) with the Water Services Board (WSB) covering the project area.

One of the benefits for WUAs is that their project artisans could become self-employed contractors for Support Organizations (SO) for building water projects for other communities in line with the water sector policy/strategy and institutions.

How to make water projects sustainable and economically viable

1. How to calculate a water tariff

The correct water tariff for a jerry can of water (20 litres) can be found by estimating all the operation costs, including funds for repairs and emergencies, for 1 month (30 days) and divide that total cost with the demand of water in 1 month. This calculation can be done as follows:

a) Demand for water

The capacity of the Kalambani-Mutha-Ndakani Water Project was designed to produce 10 litres of water for each of the 18,200 people per day which amounts to 182,000 litres = 9,100 jerry-cans of 20 litres each in a day. That amounts to 273,000 jerry cans of water in a month, excluding livestock which would drink from the usual water holes and riverbeds.

b) Capacity of delivery

The Kalambani pump station at Thua riverbed can deliver 25 cubic metres of water (25,000 litres) = 1,250 jerry cans per hour. Since 9,100 jerry cans of water are required, the pump has to be operated for: 9,100 jerry cans / 1,250 jerry cans = 7 hours and 28 minutes, say 8 per day.

c) Monthly operational costs

| Item | Cost calculation for 1 month | Ksh |

| Diesel | 6 litres x 8 hours x 30 days = 1,440 litres @ Ksh 60 = | 86,400 |

| Service of generator | Monthly service with new filters, new oil, etc. | 15,000 |

| Watchman | Monthly salary for 1 Watchman @ Ksh 2,000 | 2,000 |

| Pipeline repair team |

Monthly salary for 3 plumbers @ Ksh 2,000 PVC glue, pipe fittings, etc. |

6,000 10,000 |

| Allowance | Sitting allowance for 18 committee members @ Ksh 200 | 3,600 |

| Pump Operators | Monthly salary for 2 Pump Operators @ Ksh 2,500 | 5,000 |

| Kiosk Attendants | Monthly salary for 10 Kiosk Attendants @ Ksh 2,000 | 20'000 |

| Stationery, etc | . | 5,000 |

| Bank charges | Ledger fee, depositing income, cheques, etc. | 2,000 |

| Transportation for buying fuel |

Bus fares for 3 persons for 4 trips@ Ksh 300 = Ksh 3,600 Bus fare for 7 drums of diesel @ Ksh 500 = Ksh 3,500 |

7,100 |

| Miscellaneous | . | 5,000 |

| . | Cost of running a water project in 1 month | 167,100 |

| . | Plus 40 % to be banked for unforeseen expenses | 66,840 |

| . | Total cost of running a water project for 1 month | 233,940 |

d) Production cost for 1 jerry can (20 litres) of water

When the monthly production cost of Ksh 233,940 per month is divided by the 273,000 jerry cans of water delivered in a month, the cost is Ksh 233,940 / 273,000 jerry cans of water = Ksh 0.86 per jerry can of water. This figure can be rounded up to a water tariff of Ksh 1 per jerry can of water.

It was found that poor people are both able and willing to pay for water when it is cheaper than rates charged by water vendors. Transparency in the financial management of the water scheme also determines to a large extent the willingness to pay.

Training of project staff

Book-keeping. The committee members were trained in financial management of their water projects by means of simple book-keeping practices to ensure that the respective staff members keep proper records of income from sale of water from the kiosks as well as on money spent on buying fuel and maintenance as well as paying salaries for staff members.

Using banking systems. The members were also trained how to use banking systems for their deposits and withdrawals, including the benefits and differences between current accounts and savings accounts as well as the requirements needed to qualify for opening a bank account with an ATM card.

Pump Operations. The committee members also identified a few men having some mechanical background to be trained and employed as Pump Operators in charge of operation and maintenance of the diesel generators and electric pumps. The Pump Operators were trained in the pump houses by the supplier of the equipment to learn the right procedures in operating the expensive and complicated diesel generators powering the electrical water pumps.

Pipe Controllers. Other persons, men as well as women, who had been very active in laying the water pipes, were trained and employed as Pipe Controllers whereby they would patrol the pipelines and repair any pipe bursts.

Kiosk Attendants. Some young women who had performed actively during the construction works and who had attended secondary schools were trained and employed as Kiosk Attendants who must keep proper records of sale of water from the kiosks.

Project Accountants. A few respectable and reliable elderly persons were elected as Project Accountants who were trained and employed to compare the Kiosks Attendants' daily sale record against the water meter and bring the cash from sale of water to the safe in the project office on the same day. According to the By-laws, an election for new committee members or to reappoint the existing ones would be implemented for every 24 months.

Information Source Links

- Lakew Desta, Carucci V., Asrat Wendem-Agenehu and Yitayew Abebe (eds) (2005). Community Based Participatory Watershed Development: A Guideline. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia.

- Vukasin H. L., Roos L., Spicer N., Davies M. (1995). Production without Destruction. Natural Farming Network. Zimbabwe.