Identification of Ticks and their Control

The occurrence of ticks in Africa is one of the major limiting factors to livestock productivity. Ticks not only sucks blood thereby generally weakening their hosts if they are many enough – they also act as major disease carriers between various species of animals. There are over 13 different tick families and more than 650 different kinds of ticks in Africa. All of them suck blood and when occurring in numbers can actually kill especially young livestock by sucking alone.

In this section we only mention the most economically important species of ticks – the ones that have been identified as major carriers of the diseases mentioned under tick borne diseases.

The diseases caused by ticks are highly devastating and lead to the use of very poisonous acaricides, to which ticks develop resistance especially when not applied appropriately, for examples in low doses, which allow the strongest and most resistant to survive.

Routine use of poisons and medicine is not acceptable in organic farming, and other ways of preventing the diseases should be sought and found. Nevertheless, in some situations and under certain circumstances it can be relevant to use acaricides. Even under organic farming conditions, we sometimes have to acknowledge the fact that we are confronted with highly deadly diseases that can take away the fundament for the livestock production on a farm or in an area. At the same time, it is also very important to be aware of following:

- The blanket use of acaricide can in fact worsen the situation because it creates susceptible animals, apart from the fact

- That there are residues in the products from this animal, and

- That the development of resistance can lead to useless acaricides in some years. Other ways and methods have to be developed. In this way, organic agriculture lead the way to search for efficient and more natural ways of managing ticks and the diseases they cause.

Understanding the epidemiology of ticks and tick borne diseases

Ticks carry deadly diseases, and they are therefore called ‘vectors’ for these diseases. Control of ticks and tick borne diseases requires a thorough understanding of their epidemiology and tick-host relationship. This understanding can help making a strategy to avoid these diseases. There are big differences between the different types of ticks and tick borne diseases, e.g. in how they are geographically spread, whether they are dose-dependent or not, and whether they only affect one animal species or more. Even though there are these differences, there are important similarities between the different parasites and the host-parasite relations, which are important to notice and which can help in finding ways of managing them, as will become apparent under the description of ticks:

- Hosts (=affected animals) can acquire immunity to the ticks as well as the diseases

- The hosts can survive without becoming ill even if it is attacked by tick that carry the diseases, because they are resistant to the diseases

- Hosts can act as carriers also if they are not sick themselves, but because they are resistant to a certain level of the diseases. This is called ‘endemic stability’ and is described below.

Families of Ticks:

The main families of ticks that affect livestock in East Africa are:

1. Soft Ticks (Argas and Ornithodoros families

2. Hard Ticks (Rhipicephalus, Amblyomma, Hyalomma, Boophilus etc)

Soft ticks and their control

The soft ticks are a big problem for poultry and other small stock, but as far as literature has indicated do not seem to take a big part in transfer of diseases generally in livestock.

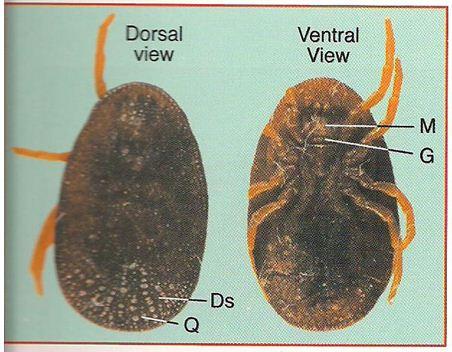

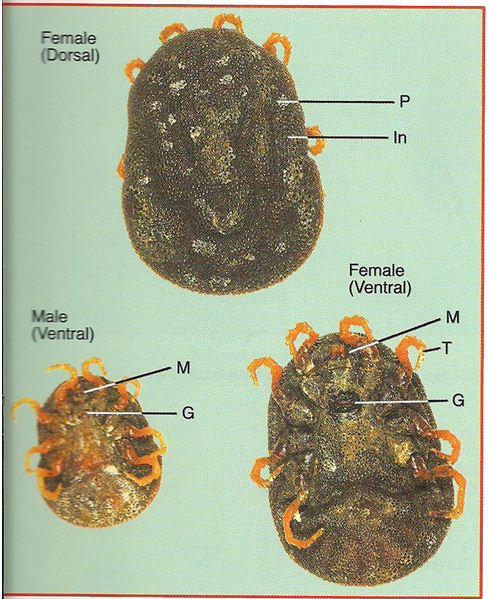

Soft ticks are usually fairly small (rarely above 5mm long). Their mouth parts are not easily seen as they sit on the underside of the tick, and their backs do not have the “Scutum” or hard back shield that the hard ticks have.

As mentioned soft ticks are mainly a problem in poultry and small stock, but they will feed on all the animals within their range. So also dogs and other domestic animals can help them spread.

The main damage of soft ticks is that they suck the blood of livestock – and when they are many the amount of blood sucked will cause animals to become anaemic, get tired and unproductive. For poultry and other small stock this can be a very serious problem, greatly affecting health and productivity of the animals.

Control measures

- As always – prevention is better than cure. Farmers have found that spreading ashes or diatomite in nesting sites and areas where the birds dust bathe, the soft tick problem can be somehow controlled or at least greatly reduced in number and thereby not affecting productivity to a noticeable degree.

- Also dry leaves of Lantana, eucalyptus, neem, pyrethrum and tephrosia added to the ashes and or diatomite in nests and dustbath areas will further reduce numbers of soft ticks.

- If the problems persist, please ask your vet about the best and least poisonous chemical dusting powder recommended for this problem.

|

|

Soft ticks (Genus Argas), picture from “Taxonomy of African Ticks” |

|

© ICIPE Science Press |

|

|

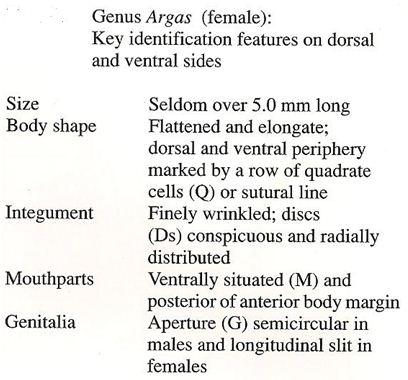

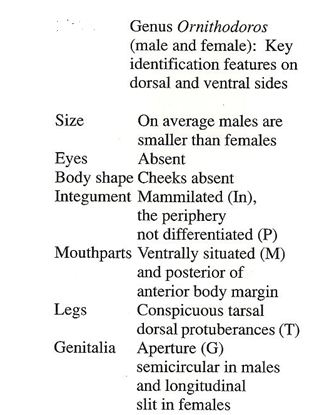

Soft ticks (Genus Ornithodoros), picture from “Taxonomy of African Ticks” |

|

© ICIPE Science Press

|

Hard ticks and their control

The main disease carriers are the following:

- The Blue tick, or cattle tick (Boophilus sp) This major family have many species each of which have different geographical distribution. The blue tick is instrumental in transferring both Anaplasmosis and Babesiosis which are both major diseases of cattle in East Africa (see below).

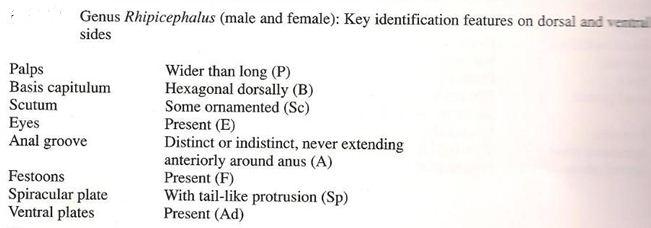

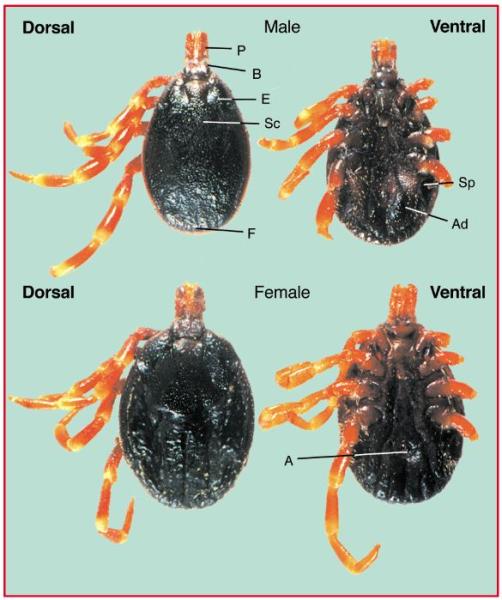

- The brown Ear tick (Rhipicephalus sp) is not always easy to distinguish from the blue tick, but whereas the blue tick can be found anywhere on the body, the brown ear tick prefers areas around the ears an under the tail. The brown ear tick is responsible for transferring East Coast Fever (ECF) in cattle and Nairobi Sheep disease. (see below)

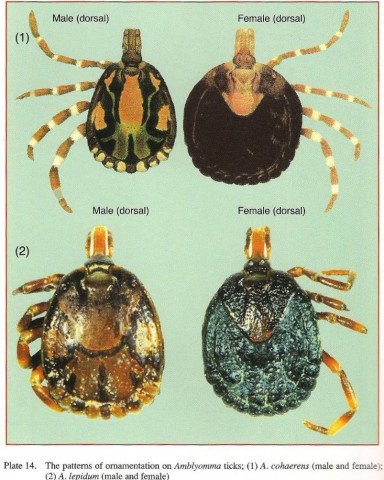

- Amblyomma ticks transfer Heartwater disease (see below). These ticks have striped legs, sometimes a distinct ornamentation on the back shield and can often be seen boring right into the skin of the animals, thereby becoming very difficult to remove by hand. Often fairly large ticks - more than 5 mm long.

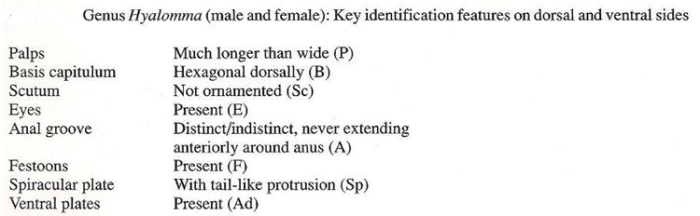

- Hyalomma ticks - often with striped legs, but no ornamentation on the back. It transfers Sweating sickness of calves/cattle (see below)

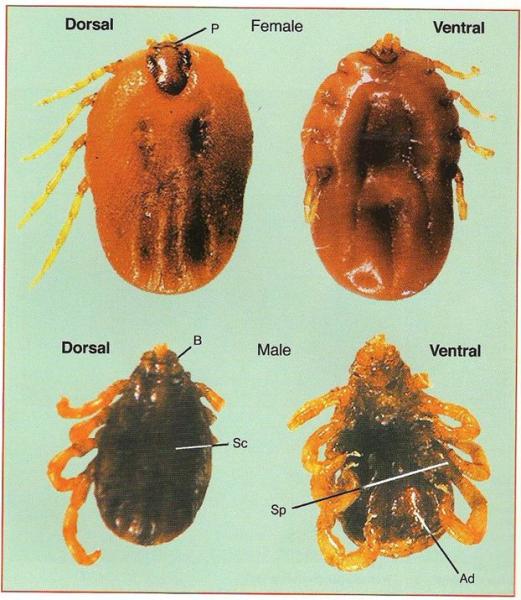

1. The Blue tick

|

|

The Blue tick, note position of grooves on the bloated tick. Picture from “Taxonomy of African Ticks” |

|

© ICIPE Science Press

|

|

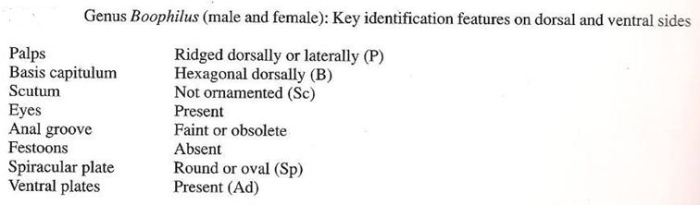

2. The Brown Ear tick |

|

|

|

| Brown Ear tick (note the slight difference in positioning of grooves on the bloated tick compared to the blue tick above). Picture from “Taxonomy of African Ticks” | |

|

© ICIPE Science Press

|

|

Ticks under the tail of a cow |

3. Amblyomma ticks

|

|

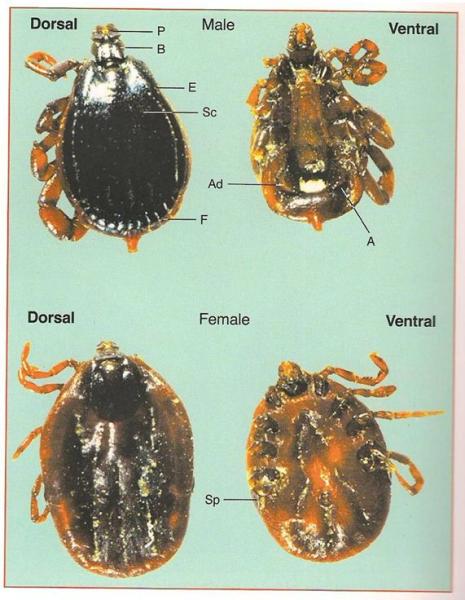

4. Hyalomma ticks

|

|

| Hyalomma ticks ticks have somehow striped looking legs but have no ornamentation on the back. They also have very strong mouth parts used to dig into the host animal. | |

|

© ICIPE Science Press

|

|

Control measures for Hard Ticks

Control measures for Hard ticks in normal livestock herds in East Africa include the following:

- Breeding for tick resistance: Use primarily local breeds which are more resistant than exotic breeds, or cross breeds.

- Hand picking of ticks, which can be done weekly or even twice per week, if the problem is very big. Try as much as possible to remove the whole tick and not only the lower part of the body. This requires some training, and experienced people can do it by ‘twisting’ the whole tick and forcing it loosen its grip in the skin. Throw the ticks immediately on the fire. If you manage to remove the whole tick and just throw it on the ground or in the grass, it is still alive and can jump on the same animal or another animal again. See below for an explanation of endemic stability.

- Dusting with diatomite or in desparate cases with dusting powder recommended by the vet containing acaricides.

- Spraying with tephrosia leaves. Tephrosia has an effect like a ‘natural acaricide’ and can kill ticks. Pick leaves from tephrosia trees and put about 500 grams of them in a 20 L bucket, which you fill up with water. You can dilute that tincture with another bucket of water. Let them stay there for a couple of days and spray it over the animals, where the ticks are.

- Spraying with knapsack or similar device. In spraying a herbal agent such as Tephrosia or pyrethrum can be used or alternatively an approved acaricide. Equipment wise there are a range of sprayers available from knapsacksprayers, over foot pumps to hand operated lever pumps.

- Spray races are expensive to put up but very effective for treating large herds of animals. Spray races normally use acaricides for efficiency and labor saving.

- Dips. These are well known in East Africa as there used to be public dips in villages where farmers could take their animals for dipping at regular intervals. However this service seems to have mostly disappeared. Large scale farmers still construct dips for their herds as it is an efficient and labor saving way of controlling ticks.

- Spraying cattle before moving them to a new pasture

- Alternating pastures and crop land. If the land is kept free of cattle for a season there is a chance that some of the ticks waiting on that land will not survive.

Reducing the need for acaricides through smart organic management

Make the animals resist the tick-borne diseases through endemic stability

In a highly susceptible cattle population, the impact of tick borne diseases can be devastating, whereas in a population constantly exposed to ticks and tick borne diseases, endemic stability can develop and reduce the problem significantly. Endemic stability build on the fact that cattle can develop resistance towards the tick borne diseases if they are constantly exposed in very small doses. That exposure keeps alive the cattles’ ability to fight the disease. Some cattle breeds – especially the local breeds – have a stronger ability to this than imported cattle breeds (so-called exotic breeds). Regular hand-picking of ticks, for example weekly or twice per week, will keep this endemic stability in a population of strong cattle with the ability to build up resistance.

Managing ticks and tick borne diseases from an organic livestock farming perspective

Routine use of acaracide treatments is unacceptable from an organic perspective. Strategies should be developed which focus on prevent the diseases and support the specific resistance of the animals to ticks and the tick borne diseases. These strategies can include:

- Preserve enzootic and endemic stability, or re-establish it through immunization against TBD, as described just above. A vaccine is now also available against ECF. Please consult you local vet for more information.

- Use the existing knowledge and educate all in the organic farming environments about the benefits gained and methods of boosting immunity to tick borne diseases, and achieving host resistance to ticks,

- Breed for increased resistance to ticks as well as to tick borne diseases,

- Develop grazing and husbandry strategies, see below for some examples.

- Use non-poisonous methods of controlling ticks in individual cases, and fitting to the situations – e.g. hand-picking of ticks and use of plant-based acaricides like tephrosia.

- Careful use of acaricides, which is a careful selection of situations where it is found relevant to use acaricides, in combination with a careful selection of the acaricide itself. This is described in details below. Even though acaricides are strong poisons, we have to face the fact that tick borne diseases and ticks are very dangerous diseases which cause great losses, and it can be necessary to use in some situations, as long as we have them available. Below, we have given a description of situations and a description of the different poisons (acaricides).

Breeding

Cattle differ widely in their resistance to ticks and tick borne diseases. Wherever possible, tick-resistant cattle should be promoted through selective breeding to increase the resistance of cattle in a herd. This will result in lighter tick infestations and reduce the requirement for acaricide treatments. Continuously selecting those animals for breeding that consistently carry the smallest number of ticks is a good and cheap strategy. Local cattle breeds are well-known for being more resistant to tick borne diseases than exotic breeds, which never had been exposed and therefore also not naturally selected for resistance.

Grass land management

Alternating between fields with crops and pasture with livestock reduces tick populations. Alternating between sheep and cattle does the same. It can be combined with treatment of cattle just before they enter a new paddock. Certain birds (oxpeckers, cattle egrets, chickens) also contribute to an overall reduction in tick numbers on livestock and on pastures, so that means that environments which favor those birds should be encouraged. Organically farmed land with no pesticide use and a good biodiversity has a good chance of doing that.

Hand picking of ticks

As explained above, hand picking of ticks can contribute to building up an endemic stability in an area, if all agree to do the same. In this way, the cattle population in a local area will all have a built up resistance and the situation is stable.

Use of natural acaricides

In some cases it can be an advantage to use natural acaricides like tephrosia , where ½ kg is soaking in a bucket of water for 48 hrs and then diluted to 2 buckets which can be sprayed on the attacked cattle, for example when there are a high number of ticks on some of the animals, and handpicking seems hopeless. On the other hand, picking leaves and preparing a solution for spraying also requires labor. One should be aware that plants can also be very poisonous, and nicotine / tabacco leaves, which were previously seen as one option for treating ticks and ectoparasites, are now discouraged by many for use in organic farming. Therefore, plant medicines and poisons should also be applied and handled with care. Always check the effect after a day or two and make sure that it has worked.

Careful use of acaricides

Many measures to avoid tick borne diseases include the use of an acaricide, which is a very poisonous chemical. There are various types of acaricides on the market and it can be difficult to know which one is best or even least poisonous to work with. Like with antibiotics, farmers also experience a lot of acaricide resistance. Below we explain about this problem and what it means to the selection of acaricides and situations to use it in on an organic farm.

Acaricide classes and resistance in ticks

|

WARNING: Improperly manufactured and wrongly applied acaricides can kill livestock and people! NEVER use acaricides to spray on vegetables!!!! |

The resistance of ticks to acaricides results from repeated long-term exposure of ticks to one and the same chemical (acaricide) and survival and reproduction of those few ticks that are less affected by this acaricide. The longer one acaricide is used, the higher the chance of ticks becoming resistant. If an acaricide is used under-strength (= too diluted to be fully effective) more ticks can survive and resistance in ticks emerges much faster. Use acaricides with care and only in situations, where no other options are possible – remember that even though it feels like doing something secure, routine use of acaricides can actually worsen the situation and undermine the possibilities for handling the situation in cases of emergency.

Ticks resistant to organophosphate and synthetic pyrethroid acaricides are widespread. But in most countries amitraz resistant ticks are not common. Changing from one acaricide class to another is also called ‘acaricide rotation’. It is helps to delay or reduce the emergence of acaricide resistance in ticks. – When you think that an acaricide is no longer working, it is good to first contact your local veterinarian and seek advice on how to react.

Different acaricides contain very different chemical substances that can kill ticks. According to the active ingredient that it contains, an acaricide belongs to a specific type or class. Acaricide of the same class all work in a very similar way. If ticks have become resistant against one acaricide in a particular class, they will also be resistant against other acaricides of the same class. This is very important when one considers changing from one acaricide, which is no longer efficient, to a different new one. Don’t just change from one product to another. Different manufacturers use different product names and different products can contain exactly the same active ingredient.

When comparing different acaricides always look for and compare the chemical name. Also, compare whether two different acaricides belong to the same class.

Acaricides are very toxic. Even skin contact with an acaricide is dangerous and can cause severe disease.

An overview of acaricide classes and chemical names is given below:

|

Name of Acaricide Class |

Different acaricides all belonging to the same class |

|

Organophosphates |

Diazinon Dichlorvos Chlorfenvinphos Coumaphos Ethion |

|

Carbamates |

Carbaryl Promacyl Propoxur |

|

Chlorinated Hydrocarbons (also called Organochlorines) Old class, no longer used in many countries |

Lindane Methoxychlor Toxaphen |

|

Pyrethrins & Synthetic Pyrethroids |

Cypermethrin Flumethrin Fenvalerate Permethrin Pyrethrin |

|

Formamidines |

Amitraz (only product in this class) Not for use in horses/donkeys |

|

Macrocyclic Lactones |

Doramectin Moxidectin Ivermectin |

Only buy and use registered acaricides and follow exactly the manufacturers’ instructions on how to use them. Besides the brand name and instructions for use the acaricide package must show the name of the chemical substance contained in the acaricide, the withdrawal period for milk and meat, the address of the manufacturer, the expiry date of the product and a health warning.

The best suitable acaricide should be cheap, easily applied, with a strong effect on female ticks to prevent them from laying eggs and to protect cattle from reinfestation by tick larvae. In addition, it should also be non-toxic to livestock and humans and have no residues in meat and milk. - Unfortunately, such an acaricide has not yet been discovered.

‘Chemical Control’ is the correct application of an efficient acaricide and remains the most important tick control strategy in the foreseeable future. - For small scale farms the best acaricide application methods are knapsack-sprays or pour-ons. Medium and large farms can use dips or spray races.

Review Process

- William Ayako, KARI Naivasha. Aug - Dec 2009

- Hugh Cran , Practicing Veterinarian Nakuru. March - Oct 2010

- Review workshop team. Nov 2 - 5, 2010

- Addition of Nairobi Sheep Disease Oct 2011 by Dr Hugh Cran

- Addition of Ticks Identification Chapter by A. Bruntse, Oct 2013

- Addition of information by Dr Mario Younan, VSF-G, October 2013

- Edited by Mette Vaarst, OrgAnimProve November 2013

- For Infonet: Anne, Dr Hugh Cran

- For KARI: Dr Mario Younan KARI/KASAL, William Ayako - Animal scientist, KARI Naivasha

- For DVS: Dr Josphat Muema - Dvo Isiolo, Dr Charity Nguyo - Kabete Extension Division, Mr Patrick Muthui - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Isiolo, Ms Emmah Njeri Njoroge - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Machakos

- Pastoralists: Dr Ezra Saitoti Kotonto - Private practitioner, Abdi Gollo H.O.D. Segera Ranch

- Farmers: Benson Chege Kuria and Francis Maina Gilgil and John Mutisya Machakos

- Language and format: Carol Gachiengo

Information Source Links

- Barber, J., Wood, D.J. (1976) Livestock management for East Africa: Edwar Arnold (Publishers) Ltd 25 Hill Street London WIX 8LL

- Blood, D.C., Radostits, O.M. and Henderson, J.A. (1983) Veterinary Medicine - A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Goats and Horses. Sixth Edition - Bailliere Tindall London. ISBN: 0702012866

- Blowey, R.W. (1986). A Veterinary book for dairy farmers: Farming press limited Wharfedale road, Ipswich, Suffolk IPI 4LG

- Brightwell R, Kamanga J and Dransfield R (1998). Key Livestock Diseases of Dryland Kenya. Kenya Economic Pastoralist Development Association (KEPDA), P.O. Box 30776, Nairobi Kenya.

- Force, B. (1999). Where there is no Vet. CTA, Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 978-0333-58899-4.

- Hall, H.T.B. (1985). Diseases and parasites of Livestock in the tropics. Second Edition. Longman

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: General principles. Volume 1 (Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN: 0333612027

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: Specific Diseases. Volume 2 (Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN:0-333-57360-9

- ITDG and IIRR (1996). Ethnoveterinary medicine in Kenya: A field manual of traditional animal health care practices. Intermediate Technology Development Group and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN 9966-9606-2-7.

- Merck Veterinary Manual 9th Edition

- Okello-Onen, J, Hassan S.M, Essuman S: Taxonomy of African Ticks, Reprint Jan 2006, ICIPE Science Press ISBN No: 92 9064 127 4

- Organic Farmer magazine No. 50 July 2009

- Pagot, J. (1992). Animal Production in the Tropics and Subtropics. MacMillan Education Limited London

- Sewell and Brocklesby. Handbook of Animal Diseases in the Tropics 4th Edition

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 51 August 2009