|

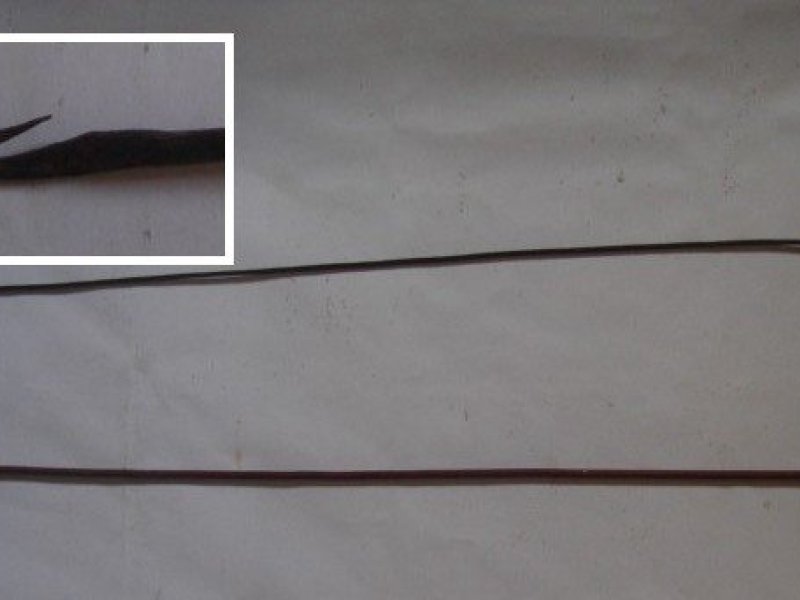

African palm weevils (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) Adults are large weevils (40-55 mm in long), with a long snout and reddish brown in colour, and generally with 2 reddish bands on the thorax. Females lay eggs on wounds of various origins, on the mature stem as well as in the crown. Upon hatching the larvae (grubs) penetrate into the living tissues of the palm, feeding on the shoot and young leaves, where the insect completes its development in about 3 months. The damaged tissues turn necrotic and decay. Sometimes the grubs feed on the growing point killing the palm. Grubs are whitish-yellow, legless, and oval in shape; their head is reddish brown, and is armed with strong mandibles. Fully-grown grubs are 50 to 60 mm long. The pupal stage is passed within a cocoon of vegetal debris made by the grub at the end of its development. The African palm weevil usually damages young palms, yet may also, in exceptional cases, cause damage to mature crops.

The primary means of control for African palm weevil is preventative, using cultural and sanitary methods.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

African rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes monoceros) It is a stout beetle, about 3.5 to 5 cm long, shiny dark brown to black in colour with a curved horn on the head, hence its common name. The adult flies at night to palms and bore into the hearth of the palms spear, chewing and cutting the youngest unopened leaves and the vegetative bud. Attacked leaves continue to develop and unfold showing a characteristic V-shape damage. If the whole growing point is eaten, the palm usually dies, particularly young palms less than four years old. The boreholes are often marked with a bundle of fibres pushed out of the hole by the beetle. This beetle is a serious pest in plantations where field sanitation is neglected. Eggs are laid in rotting plant material, especially dead palm trunks, compost heaps and rubbish dumps. The larvae (grubs) and pupae develop in rotten coconut logs and other decaying material.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Bud rot (Phytophthora palmivora) Bud rot (also called heart rot) caused by the fungus Phytophthora palmivora has an extensive host range of more than 200 plant species and it is widespread in the tropics including tropical Africa. The fungus enters into the plant by infecting tender host tissues (leaves, buds or young nuts). Affected leaves turn yellow and later brown.

The heart leaf becomes chlorotic, wilts and collapses. The disease may spread to older, adjacent leaves and spathes, producing a dead centre with a fringe of living leaves. Light brown to yellow, oily, sunken lesions may be found on leaf bases, stipules or pinnae. Internally, the tissues beneath the bud are discoloured pink to purple with a dark brown border. Affected leaves progressively drop. Infected nuts show brown to black necrotic areas with a yellow border developing on the surface; internally, they have a mottled appearance. Young nuts are highly susceptible and fail to mature, they then fall off the tree; older infected nuts ripen normally.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Adult coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) The coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) is the most important pest of coconuts in East Africa. A related species of coconut bug, Pseudotheraptus devastans, causes similar damage to coconuts in West Africa. Adult bugs are brown in colour and 1.2 to 1.4 cm long. They lay eggs singly on the flowers or young nuts. Nymphs are red brown to green brown in colour and have long antenna. Adults and nymphs suck on flowers and developing fruits causing flower abortion and early nutfall. The toxic saliva of the bugs causes necrotic sunken lesions (scars) and cracks on the nuts. Attacked young nuts excrete gum. Many of the attacked young nuts fall off. Nuts older than 3 months at the time of attack may not be aborted but remain small and have scars. Yield losses are difficult to assess since many of the nuts (over 70%) fall naturally. Nuts which abort naturally, do not show scars or gummosis. Two bugs per palm can cause considerable damage. Damage is usually less serious in intercropped coconuts. The bugs also feed on cashew, mango, cocoa and guava. The predatory red weaver ant is an efficient natural enemy of the coconut bug. Weaver ants build nests on palms and other trees by joining leaves with silk produced by their larvae. They forage on the canopy chasing away or killing coconut bugs. Palms with weaver ants are usually free of damage by the coconut bug. Good control is achieved when more than 60% palms are occupied by thriving colonies of weaver ants. Unfortunately other ants present in coconut plantations fight weaver ants, and themselves do not protect (or not as effective as weaver ants) the palms against coconut bugs. These ants such as big headed ant (Pheidole megacephala), the crazy ant (Anoplolepis custodiens), and the long legged ant (Anoplolepis longipes) among others, kill or displace weaver ants, as a result palms are severely damaged. These competing or antagonistic ants need to be managed to allow weaver ants to do their beneficial work. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Coconut mite (Aceria (=Eriophyes) guerreronis) This mite is tiny and difficult to see with the naked eye. When very many mites are together they appear as fine whitish dust. The coconut mite attacks and damages the upper part of the nutlets under the sepals of up to 6 months old nutlets. Attack is severe during the dry season. Attacked nuts may fall or have a scarred husk, which often splits. The nuts of coconuts showing light scarring on the husk are not seriously affected but in heavily scarred nuts there is significant damage to the nuts.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Lethal bole rot (Marasmiellus cocophilus) In East Africa, Marasmiellus cocophilus causes death of palms up to 8 years old, seedlings being highly susceptible on transplanting to the field. Root infections occur, leading to decay of basal tissues and finally a rot of the spear leaf. On older palms, the first symptoms are a general wilt of the fronds, which remain as a 'skirt' around the trunk. The spear leaf dies and a foul-smelling soft rot develops at the base of the leaves. A dry, reddish-brown rot with a yellow margin is typically present at the base of the bole. Cavities within these areas of rot are lined with mycelium (fungal growth) in young palms, 2-4 years old, but rare in 4-6-year-old palms, and absent in mature palms. Fungal bodies (like small mushrooms) commonly occur on exposed roots, leaf bases of seedlings, exposed tops of seed nuts and on the soil surface around holes (growing from coconut debris) where diseased palms had been removed 2 years previously. On average, there is only about 8 weeks from the time of onset of symptoms till the death of the palm; this interval depends on the extent of fungal decay in the bole. Spread occurs through soil, root contact between palms, infected coconut debris and probably by airborne basidiospores (fungal spores). Infection also occurs via wounds.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Lethal yellowing (Phytoplasma) Symptoms include necrosis of inflorescences, yellowing of leaves and premature shedding of all fruit (nut fall) regardless of their developmental stage. Aborted nuts often develop a brown-black calyx-end rot reducing seed viability. Premature nut fall is accompanied or followed by inflorescence necrosis. This symptom is most readily observed as newly mature inflorescences emerge from the spathe. Normally light yellow to creamy white in colour; affected inflorescences are instead partially blackened (necrotic) usually at the tips of flower spikelets. As disease progresses, additional emergent or unemerged inflorescences show more extensive necrosis and may be totally discoloured. Such symptom intensification results in the death of most male flowers and an associated lack of fruit set. Yellowing of the leaves usually starts once necrosis has developed on two or more inflorescences and discolouration is more rapid than that associated with normal leaf senescence. Yellowing begins with the older (lowermost) leaves and progresses upward to involve the entire crown. Yellowed leaves turn brown, desiccate and die. In some cases, the advent of this symptom is seen as a single yellow leaf (flag leaf) in the mid-crown. Affected leaves often hang down forming a skirt around the trunk for several days before falling. A putrid basal soft rot of the newly emerged spear (youngest leaf) occurs once foliar yellowing is advanced. Spear leaf collapse and rot of the apical meristem invariably precedes death of the palm at which point the crown topples away leaving a bare trunk. Infected palms usually die within 3 to 6 months after the appearance of the first symptoms. Lethal yellowing symptomatology may be complicated by other factors. For example, non-bearing palms lack fruit and flower symptoms. Foliar discolouration also varies markedly among coconut ecotypes and hybrids. For most tall-type coconut palms, leaves turn a golden yellow before dying whereas on dwarf ecotypes leaves generally turn reddish to greyish-brown. Phytoplasmas are transmitted in a persistent (circulative-propagative) manner primarily by insect vectors belonging to the families Cicadelloidae (leafhoppers) and Fulgoroidae (planthoppers).

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mealybugs Mealybug infestations of above-the ground plant parts start with the appearance of crawlers (the first- instar nymphs) on the underside of the leaves on terminal shoots, stems and other plant parts. Heavy mealybug attack appears as white, waxy masses of mealybugs on stems, nuts and along the veins on the underside of leaves. Heavy infestations usually result in coating of adjacent stems, leaves and nuts with honeydew and sooty mould. Severely infested plants may wilt due to sap depletion; leaves turn yellow, gradually dry and ultimately fall off. Feeding on nuts results in discoloured, bumpy, and scarred nuts, with low market value, or unacceptable for the fresh fruit market. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

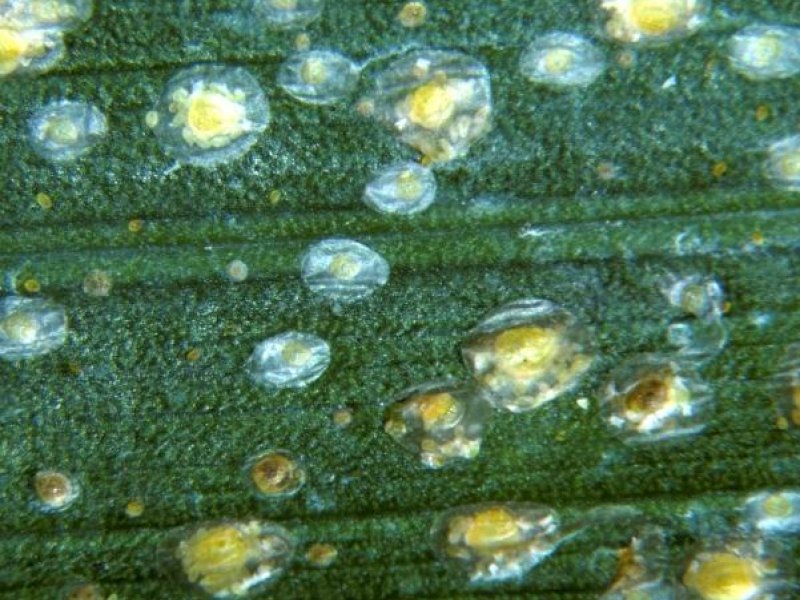

Coconut scale (Aspidiotus destructor) A number of scales feed on leaves and fruits of coconut palms. The most damaging is the coconut scale (Aspidiotus destructor). This scale is bright yellow and round (females) or reddish and oval (males) covered with a semitransparent greyish white flat scale. The scale diameter is 1.5 to 2.0 mm. Females are always wingless and remain under their scale their entire life. Adult males have one pair of membranous wings, move about actively in search of females and do not feed during the adult stage. Eggs are protected underneath the scale or shell of the mother insect until they hatch. Upon hatching the young scales leave the maternal scale, take up a position and start feeding. They do not move afterwards. They are found mainly on the undersides of the leaves, but frond stalks, flower clusters and young nuts can also be attacked. A severe infestation of this armoured scale forms a continuous crust over flower spikes, young nuts and the lower surface of leaves. The leaves become yellow and eventually die. The crown dies leading to collapse of the infested plant. Attacks of young nuts cause shrivelling of nuts leading to premature nut falls. Mostly young coconut trees of up to 10-15 years are vulnerable to damage. Scales may infest palms throughout the year, but damage is usually more severe during the dry season. Neglected plantations are particularly susceptible. The coconut scale also attacks many species of fruit trees, such as avocado, breadfruit, mango, guava and papaya. Other major hosts are cocoa, cassava, cotton, oil palm, papaya, rubber, sugarcane and tea. It also attacks a range of ornamental plants including roses.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Termites (Coptotermes formosanus) Termites can be a serious problem for coconut palms, particularly for young trees in tree nurseries or trees that have just been transplanted into the field. Termites live in the soil in hills, construct tunnel from the hills to the palms and feed on all parts of young coconut palms. Damage occurs mainly during the dry season. Many plants have a repellent or even insecticidal effect on termites and can be applied as spray directly against termites or as barrier around the trunk of coconut palms:

Euphorbia sp.: "In Tanzania, especially in Dar es Salaam and coast regions, farmers plant with each seedling 2 or 3 sticks of Euphorbia sp. to protect the young palms from termite attack. On nurseries the Euphorbia plants can be planted around the seedbed to prevent access of termites to the palm seedlings and young palms. When the palms have grown big the euphorbia is simply cut down. The practice is widespread and farmers are convinced that it really does keep termites off the susceptible seedlings (Z. Seguni, MARI personal communication)".

|

|

|

What to do:

|

Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Coconut in Africa. Updated on 8 July 2019. source FAOSTAT

© OpenStreetMap contributors, © OpenMapTiles, GBIF.

Read more

Local names (Detailed)

Benin: Agonkèdo (Fon); Agonkè; Agonkèssin

Cameroon: Coconut palm (Fundong)

DRC Congo: Ba di nkandi (Kongo), Cocotier (French)

Ghana: Kube (Twi dialect)

Guinea Conakry: Cocotier (French)

Kenya: Mnazi (Mijikenda); Naas(Luo); Munathi (Kamba); Mnazi(Swahili); Enasi(Suba)

Mauritius: Cocotier (Creole); Taynay Marum (Tamoul)

Madagascar: Vanio (Antakarana); Nio (L’arbre); Dafo, Kamba, Kaopra (Amande Sèchée); Voaniho, Voanio (Le Fruit) (Malgache); Cocotier (French); Coco (Betsimisaraka)

Nigeria: Agbon, Agbo (Yoruba); Aku Oyinbo (Igbo); Mosara (Hausa)

South Africa: Kokospalm (Afrikaans)

Togo: Netsi, Kpakpadirè (Tem)

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

Introduction

The coconut (Cocos nucifera) is a tropical plant that belongs to the palm tree family (Arecaceae) and the only species under genus Cocos. However, there are numerous cultivars and varieties of coconuts, each with its own unique characteristics and economic value. Coconut palms Cocos nucifera L. (French.: cocotier; Spanish.: cocotero) originate from Melanesia. South East Asia is still an important cultivation region today. The coconut is a monocotyledon plant, and can therefore only proliferate via seeds. It can produce an inflorescence on each leaf axil, which can then have either male or female blossoms. These are formed on the side, so that generally, the coco palm is cross-fertilised by a variety of bee species, other insects and the wind. Coconut palms live to an average age of 60 years old. The coconut has been spread since antiquity to many tropical regions around the world, particularly warm humid coastal ecosystems. It thrives in sandy coastal areas with high humidity and abundant sunlight. Ecologically, coconuts play a vital role in coastal ecosystems. They have adapted to tolerate saline conditions and their root systems help prevent soil erosion. The trees also provide habitat and nesting sites for various bird species.

The coconut palm is an important tree in most tropical islands and along the coastal regions of tropical Africa. Coconut palm is a versatile tree that offers a wide range of application with every part of the plant being utilized. The most widely known usage is as a food resource. The water inside the young green coconuts is rejuvenating and nutritious, while the white flesh referred to as the coconut meat is rich in healthy and balanced fats and can be consumed raw, dried, or utilized in food preparation. The juice from the inflorescence, which can contain up to 15% sugar, is used to make palm-wine. Half-ripened nuts (6-7 months old) are often eaten fresh. The juice can be drunk, and milk is squeezed out of the meat (endosperm). Fully ripened nuts (after 11-12 months) provide the so-called copra, which is made from the firm meat of the nut. Copra is high in oil and protein content (65% oil, 25% protein). Coconut oil is produced from drying and pressing the copra. The hard coconut shells are used to make charcoal. When they have been finely grated, coconut shells are used as fillers for objects made of plastic, such as buttons, containers and other objects.

Coconut oil derived from the meat, is widely used for food preparation, skin care, and also hair treatment products. Medicinally different parts of the coconut tree are utilized. Coconut oil is thought to have antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties and coconut water is commonly utilized as a natural rehydration option. Coconut fibres are used in the upholstery industry, to make ropes, as mulching material or as a substitute for peat. The leaves and wood are used as building material and to make household objects (e.g., baskets, brooms) and tools

Coconuts are incorporated into a wide range of dishes across different cuisines. From curries, desserts, and beverages to sauces and marinades, coconuts add a distinctive tropical flavor and creamy texture to many recipes. Coconut milk, made by blending grated coconut meat with water, is a popular ingredient in the diets of many people in the tropics and subtropics. Coconuts are a valuable source of nutrition. They are rich in healthy fats, dietary fiber, vitamins (such as vitamin C, E, and B-complex), and minerals (including potassium, manganese, and copper). They provide energy, promote heart health, aid digestion, and support immune function (Van der Vossen & Chipungahelo, G.S.E, 2007, plantvillage).

Species account

Cocos nucifera is a tall, evergreen tree that can grow to a height of up to 30 meters with a sturdy trunk with a smooth, grayish-brown bark. Leaves: long, feather-like leaflets arranged in a symmetric pattern along the central rib, dark green in color. Flowers: coconut tree is monoecious, producing both male and female flowers on the same tree, can be white to pale yellow. Inflorescence: is a spike produced at the leaf axil with 20–60 branches, each with a female flower at the base and many male flowers2.

Fruit: is a drupe, typically oval or round-shaped, and can grow to be about 30 centimeters (12 inches) in diameter. It features a hard, fibrous outer husk surrounding a thick, woody shell that encloses the edible white meat, known as the copra, and a refreshing liquid called coconut water.

The coconut is a monocotyledon plant, and can therefore only proliferate via seeds. Coconut palms live to an average age of 60 years old (Van der Vossen & Chipungahelo, G.S.E, 2007, plantvillage2).

|

ⒸAdeka et al., 2005 |

|

Ecological information

Site requirements

Coconut needs a continuous supply of water, which can be provided by regular rainfall of about 1250 mm per annum, or from ground water (at a depth of 1-3 m). It cannot tolerate water logging. The northern Kenya coast receives only a rainfall of 750-1000 mm and this restricts production. Coconut grows best at average temperatures of around 26-27deg C. Because of its temperature requirements, the coconut palm cannot normally grow above 750 m. However, near to the equator and in areas where other conditions are favorable for coconut development, it is possible to grow the crop up to about 1300 m. Growth is stimulated by a sufficient supply of chlorine in the soil. The coconut palm can withstand up to 1% salt in the soil.

These conditions are generally found in tropical and subtropical coastal regions with little rainfall. Coconut palms can also grow on deep, water-logging free, alluvial soil, away from the coast - yet low chlorine content in the soil could have negative effects. Consider these conditions when choosing a site.

Depending on the site, coconut palms can be cultivated on agroforestry systems. As a plant of the upper storey, with essential light requirements, the coconut palm towers above such crops as citrus, cacao and others.

Agronomic aspects

Seeds

The quality of the seeds is important for the forthcoming yield from the palm. For this reason, the seeds should originate from a healthy, productive stock plant. Usually, the seedlings are raised in state and private tree nurseries. If no tree nursery can be found which comply with the requirements of organic cultivation, then the seedlings will have to be raised on the site.

Two different main groups are cultivated in the commercial sector: the tall plants of the Typica group, which generally need to be cross-fertilized, and dwarf types of the Nana group, where self-pollination is the norm. Tall varieties should always be chosen for agroforestry systems, because they can reach up to the upper levels intended for them, and thus fully develop. Dwarf palms grow very slowly, and are easily overshadowed in the system, hindering their full development. In addition, the Nana variety reacts more sensitively to drought and some diseases than Typica varieties.

Three distinct types grow in Kenya: the "East African tall", the "Pemba Dwarf" and hybrids. The following hybrids have been introduced to increase yields and quality of coconut in Kenya:

• "PB 121" ("Malayan Yellow Dwarf" x "West African Tall")"

• A72" ("Green Dwarf" x "West African Tall")

• "Tahiti Tall" x "West African Dwarf"

• "Yellow Dwarf" x "Tahiti Tall"

• "Reussell Tall" x "West African Tall"

The hybrid "PB 121" has shown to be particularly high yielding (Griesbach., 1992).

Before sowing, the nuts are sorted; use only those nuts containing water. Cut away the shell on the germinating side of the nut to facilitate germination, and soak the nuts in water for 14 days, before sowing them in loose soil that can drain easily. Lay the nuts lengthways in the soil with the upper side visible. Sow nuts in nursery beds at a distance of 45 cm. Use coconut fibres as mulching material between the rows leaving the planting area uncovered. On smallholdings, the nuts are often merely set out in shaded areas, lightly dug in, and then covered over with organic material.

Planting methods

Nuts usually begin to germinate after 12 weeks in the nursery beds. There, they require no additional fertiliser, as the endosperm provides them with sufficient nutrients. When the seedlings are planted in beds dry season, then the beds need to be irrigated 2 times a week with around 5 l water/m2. Select the strongest seedlings after the 5th month and label them for transplanting. Around 20-40 % of the seedlings will be unusable. Suitable seedlings germinate earlier, and have thicker leaf bases. Early leaf-development is a sure sign of a strong plant. Transplant seedlings after 9-10 months, by that time they should have developed 4-5 fully opened leaves. Remove seedlings from the nursery beds, shorten their roots, and plant again as soon as possible.

The distances between the plants should be between 7.5 x 7.5 m and 6 x 9 m, depending on the cultivation method used and the other crops being grown, or similar distances resulting in an average density of 150-180 trees/ha. The recommended normal spacing for tall hybrids is 8 x 8 m or 9 x 9m, and for dwarf hybrids 7 x 7 m. The planting holes should be about 60 cm deep and 60 cm in diameter. The planting hole should be dug at least 1 month before planting and immediately filled with a mixture of topsoil, wood ash and well-rotted manure which is allowed to settle. Transplanting should be done at the beginning of the rains. Place the plant in the hole about 30 cm below the soil level. Fill the remaining space in the hole gradually as the palm becomes bigger. By using this planting method the palms are less susceptible to drought. This method should not be used when the ground water is relatively high. The nut should be earthed up only to the collar of the shoot to avoid soil entering the leaf axils. The young seedlings need to be protected from animals (cattle and other livestock).

Diversification strategies

Organic coconut cultivation does not allow for mono-cropping. Existing plantations can be improved by sowing at least 1 bottom crop of plants that offer ground coverage. Legumes can be planted here as green fertilizers. In multi-level agroforestry systems, cacao, bananas, pineapples and many other crops can be used. Spices such as ginger and turmeric also thrive under palms. If animals are kept, fodder crops should be integrated in a crop rotation system underneath the coconut palms.

If possible large plants should be used from the nursery beds when setting up agroforestry systems including coconut palms. This applies not only to coconut palms, but also to all types of palms integrated within agroforestry systems. Coconut palms will grow on any sites that are suitable for cacao, bananas, citrus (oranges) or papaya. On citrus plantations, a slightly lower density should be used (120-150 plants/ha) than for cacao (150-180 plants/ha). Three phases can be identified in the development (life cycle of the coconut palm) of the crop:

|

Life cycle |

Shade |

Mixed crops |

|

1st phase: up to 8th year |

A full frond will only have developed after 8 years; during this time, only partial shade is available |

Cultivation of annual crops possible. |

|

2nd phase: from 8-25th year |

Comparatively large amount of shade |

Cultivation of shade-tolerant varieties |

|

3rd phase: older than 25 years |

Shade reaching to the ground diminishes as trees attain full height |

High amounts of sunlight allows cultivation of plants needing lots of light. |

Nutrient supply and organic fertilization

The level of nutrient extraction on a coconut palms/mixed crop system can be balanced by encouraging the decomposition of organic material that is made available, e.g. through mulching material, green fertilizer and tree trimming. A dense crop of legumes or use of other plants providing ground coverage as bottom crops, and which are regularly supplied with mulching material, will provide a sufficient supply of nitrogen for the plants. It is important to take care that all harvest and processing residues, such as coco fibers and press-cakes from the oil-extraction process, are returned to the plantation. This also applies to the potassium-rich ash resulting from burning the coconut husks. If insufficient organic material is produced on the plantation, the deficit can be balanced by regularly adding compost.

The compost should be enriched with any wood ashes (or coconut husk ashes) that are available. The compost is spread out in a circle 3-5 m underneath the palms, and preferably covered over with coconut shell mulching material. The latter may be especially necessary in systems lacking enough additional vegetation.

A deficiency in potash will result in a large reduction of yield for coconut palms. The vast majority of the potassium is thereby contained in the fruit water of the coconuts. On cultivation systems which include cacao, returning the cacao shells to the site will supply sufficient potassium to balance out the extraction. The continual pruning of crops on diversified agroforestry systems provides an important source of nutrients (potassium).

When providing a nutrient supply to coconut palms, it should be noted that it can take up to 36 months before inflorescence begins. This means that measures to supply nutrients, or to counteract deficits or other morphological disturbances, will take 3 years before they have an effect on production.

Due to their symbiosis with endomycorrhizae fungi (phosphate supply), and their tolerance of soil salts (which are often harmful to the other crops), coconut palms, as well as other varieties of palms, have a beneficial effect on the growth of the other crops in an agroforestry system.

Keep area around the tree free of weeds. Coconut will suffer from too much competition from weeds and bush regrowth. Recommended weed control methods include slashing by hand or grazing by cattle. Avoid weeding with mechanical implements as these can damage the roots of the tree. The economic life of a coconut tree is about 25-30 years. After this period, the low producers, dead and diseased trees should be removed from the field and replaced with new seedlings.

Crop monitoring

The nuts ripen during the entire year. As a rule, a harvest is carried out every 1-2 months, when the ripened coconuts are harvested directly from the tree - farmers should not wait until the nuts fall from the tree. The nuts are fully ripened when the coconut water can be clearly heard sloshing against the inside when they are shaken. Harvesting too early can unfavorably affect the quality of the copra.

Harvest, post-harvest practices and markets

Harvesting

Stock plants that are suitable seed providers produce 100 nuts per year and up to 180 g copra per nut. In drier areas yields are usually 15-20 nuts/tree/year. Harvest fully-ripened nuts intended to provide seeds after 11-12 months. Cut down nuts and lower them carefully (e.g. by rope). Do not allow the nuts to fall down. Following the harvest, store nuts for a short break in a covered, well- ventilated place. (Naturland.., 2000).

Post-harvest harvest practices

Copra drying

• Sun drying

Remove the husk first. Dry nuts on a clean surface to reduce moisture from 45% to 6%. In fine weather this takes about 5 days. Turn the pieces occasionally and cover them at night and in rainy weather.

• Kiln drying

Make a fire in the pit of the kiln. Use the coconut shells as fuel as they heat well and smoke little. Put the copra on a wire mesh platform over the fire and protect it from the rain. This takes about 4 days.

Value addition and markets

Coconut has diverse applications and significant value addition potential. It finds markets in the food industry, beverage industry, cosmetics and personal care sector, health and wellness products, industrial applications, and bioenergy.

Indonesia is the world's leading coconut producer in 2021, with about 17.16 million metric tons of coconuts produced. Other countries that produce significant amount of coconut include the Philippines and India. According to 2021 reports, the largest producers of coconuts in Africa include Ghana, Tanzania and Mozambique, with a combined 56% share of total production. Other countries producing Coconuts in Africa include Nigeria, Kenya, Comoros, Cote d'Ivoire, Sao Tome and Principe, Madagascar, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau (Source: https://www.indexbox.io/store/africa-coconut-market-report-analysis-and-forecast-to-2025/)

Nutritional value

Coconut is a high caloric and a low sugar fruit which is highly nutritious, and commonly used for its water, milk, oil, coconut cream, and tasty meat. The fruit has also become increasingly popular for their flavor, culinary uses such as, yogurt, rice dishes, coconut cakes, muffins, doughnuts and chapati preparation, and many potential health benefits.

Coconut is rich in healthy fats, primarily in the form of medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs)2. These MCTs are easily absorbed by the body and are known to provide a quick source of energy. Unlike long-chain fatty acids, MCTs are rapidly metabolized by the liver and can even aid in weight management by increasing satiety and boosting metabolism.

Furthermore, coconuts are rich in dietary fiber that play a crucial role in digestive health, promoting regular bowel movements, and preventing constipation. Consuming a fiber-rich diet may contribute to weight management, as it promotes feelings of fullness and reduces overeating2. In addition to fats and fiber, coconuts contain essential vitamins and minerals. They are a notable source of manganese, which supports bone health, metabolism, and antioxidant activity2. Coconut also provides small amounts of potassium, magnesium, and copper, all of which play vital roles in maintaining overall health and well-being.

Coconut products, such as coconut milk and coconut oil, have gained attention for their potential health benefits. Coconut milk is a creamy alternative to dairy milk and can be a suitable option for individuals with lactose intolerance or dietary restrictions. Coconut oil, extracted from the fruit's flesh, is high in saturated fats but consists primarily of lauric acid. Lauric acid has antimicrobial and antifungal properties, supporting the body's immune system and fighting off pathogens. Incorporating coconut into a balanced diet can offer several health benefits. The MCTs present in coconut may enhance brain function and cognitive performance. They have also been linked to improved heart health by raising levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, commonly referred to as "good" cholesterol. Additionally, coconut consumption may help reduce inflammation in the body, potentially benefiting individuals with inflammatory conditions.

Despite its impressive nutritional profile, it's essential to consume coconut in moderation, as it is calorie-dense. Opting for fresh coconuts or unsweetened coconut products is recommended to avoid added sugars and excessive calorie intake (infinitylearn.com 1, healthline.com2,)

Figure 3: Approximate Nutritional composition of 100g of coconut

Code Food Name |

Coconut, fresh, mature fruit, flesh |

Coconut, fresh, young or immature, flesh |

Coconut meat, dried (desiccated) |

Recommended daily allowance (approx.) for adults a |

Edible conversion factor |

0.48 |

1 |

1 |

|

Energy (kJ) |

1740 |

736 |

2730 |

9623 |

Energy (kcal) |

423 |

176 |

663 |

2300 |

Water (g) |

37.1 |

68 |

4.3 |

2000-3000c |

Protein (g) |

4.4 |

2 |

6.7 |

50 |

Fat (g) |

39 |

10.8 |

63.7 |

<30 (male), <20 (female)b |

Carbohydrate available (g) |

8.5 |

17.3 |

7.6 |

225 -325g |

Fibre (g) |

10.1 |

1 |

16.1 |

30d |

Ash (g) |

1 |

0.9 |

1.6 |

|

Minerals |

|

|

|

|

Ca (mg) |

18 |

34.7 |

25.7 |

800 |

Fe (mg) |

2.3 |

1.2 |

2.7 |

14 |

Mg (mg) |

47 |

35 |

88.8 |

300 |

P (mg) |

146 |

56 |

210 |

800 |

K (mg) |

125 |

266 |

536 |

4,700f |

Na (mg) |

29 |

12 |

36.5 |

<2300e |

Zn (mg) |

0.73 |

0.42 |

2 |

15 |

Se (mcg) |

3 |

4 |

3 |

30 |

Bioctive compounds. |

|

|

|

|

Thiamin (mg) |

0.08 |

0.03 |

0.08 |

1.4 |

Riboflavin (mg) |

0.08 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

Niacin (mg) |

1 |

1.2 |

0.6 |

18 |

Dietary Folate Eq. (mcg) |

14 |

20 |

9 |

400f |

Vit C (mg) |

2.6 |

5.8 |

2 |

60 |

Source (Nutrient data): FAO/Government of Kenya. 2018. Kenya Food Composition Tables. Nairobi, 254 pp. http://www.fao.org/3/I9120EN/i9120en.pdf

a Lewis, J. 2019. Codex nutrient reference values. Rome. FAO and WHO

b NHS (refers to saturated fat)

c https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/water/

d British Heart Foundation

e FDA

f NIH

g Mayo Clinic

Recipes

The use of coconut as a flavouring is widespread in the coastal parts of East Africa. Both the milk and the flesh are used. The milk is often added to traditional vegetables and sauces to enhance flavour. Coconut milk is used to cook rice (Biriani), fish, meat, porridge, starches such as cassava, sweet potato and banana and also pulses such as pigeon peas and beans.

Coconut milk is made from the flesh of a mature coconut. There are two forms, thick (concentrated) and light (diluted) milk. The grated coconut is squeezed to produce concentrated milk and rinsed with warm water to produce weaker milk. The last weak milky water is used for cooking while the concentrated milk is added last to flavour the food. The process may vary from community to community.

1. Tui (coconut milk)

(Coastal East Africa)

Ingredients:

• Mature coconut

• Hot water

In a bowl, combine equal parts near-boiling water and also fresh grated coconut flesh or desiccated coconut (dried, shredded).

Stir well and allow the mixture to stand for up to an hour.

Squeeze the mixture very tightly in your hands, or run it through a blender.

Strain everything through a fine cloth, using the cloth to wring all liquid from the coconut flesh. The product is concentrated milk.

To make light (thin) coconut milk, repeat the process, using the same (used) coconut flesh. The product is ‘thin’ milk. Discard the used coconut ‘flesh’.

If using canned unsweetened coconut milk, shake the can before opening. Divide the contents of the can into two parts, placing about two thirds of the can's contents in one measuring cup and the remaining one third in the other. Add enough warm water to each to make two cups. The first then becomes the "thick", the second is the "thin".

Source: Maundu et al. 2005.

2. Fried Dagaa (Silver fish).

Source: Tanzania

Ingredients

Small fish (dagaa)

Oil

Green pepper (hoho)

Curry powder

• Wash the small fish with hot water and dry the water

• Heat oil and cook onions to brown colour

• Add green pepper (pilipili hoho), curry (bizari manjano and bizari tomato)

• Put the small fish to fry and cook for 10 mins.

• Add grated carrots and tomatoes and stir

• Add the 2nd coconut milk prepared with hot water then stir and mix.

• Add 1st coconut milk and stir for 5 mins.

• Serve.

Source: Maundu and Imbumi, 2006

3. Mahamri (Bun)

Notes: mahamri and the related mandazi (Kiswahili) (imandazi, ibitumbula in Rundi) are very popular types of buns in East African restaurants.

In mahamri, the dough is usually prepared from coconut milk and yeast. It is left to stand for some hours before it is cooked in oil.

Occasionally, the dough may also be a mixture of wheat and rice flour and yeast in coconut milk. Such mahamri are often called vitumbua in some areas. Mahamri are very popular in coastal restaurants while mandazi (made with baking powder) are more common inland. Both are usually served with tea, coffee, soft drinks etc. In Dar es Salaam it is usual to eat mahamri with cooked beans (maharage). The mixture is called zege and it is eaten along with tea for breakfast.

4. Kunde za chikololo

(A recipe of the Mijikenda of Kenya)

Ingredients

1/2 kg ground cowpeas

120 g onions

200 g tomatoes

1½ teaspoonful chicken flavouring

1 cup coconut milk

Preparation

• Grind the dry peas coarsely to the size of rice grains and remove the outer coat

• Soak the cowpeas for about 5-6 hours. This shortens the cooking time.

• Discard the soaking water and add enough to boil the peas until they feel soft when pressed between the fingers (1.5-2 hrs.)

• When cooked, drain excess water and put this aside

• Heat oil, add the onions and fry slightly

• Add the tomatoes, stir then add the peas

• Add the flavouring into the coconut milk and mix well. Add this mixture to the cooking cowpeas.

• Add salt to taste, simmer and allow to cook for 15-20 minutes

• Serve with preferred starch e.g. ugali, rice, cassava, chapati or bread.

Note:

Serves 6 people

Kunde za chikololo is a very nutritious soup, rich in proteins.

When whole cowpea grain is used (not ground), the product is called “Kunde za mahinjiri”. Alternatively the dry peas can be roasted, outer coat removed and the split peas cooked instead of grinding. The peas make a thick sauce that is best served with chapati or rice.

Source: Maundu et al., 2005.

6. Majani ya Kunde (Cowpea leaves)

Ingredients

150 g cowpea leaves

100 g onion

50 g tomatoes

1 tablespoonfuls cooking oil

2 tablespoonfuls groundnut flour

¼cup coconut milk

Aromat 1 teaspoonful (optional)

Salt to taste

2 cups of water

Preparation

Select the tender cowpea leaves, wash and cut finely

Boil water, add salt and cowpea leaves and let it boil for 4 minutes while covering the pan

Wash, peel and chop the tomatoes

Clean, wash and chop the onion

Fry the onions lightly, add tomatoes and stir

Add boiled cowpea leaves, stir well and simmer for 5 minutes. You may mash the cowpea to soften

Mix coconut milk and groundnut flour and add into the vegetable while stirring for 3 minutes

Season to taste and serve while hot as a relish

(Source: Maundu et al., 2005.

| Mealybug infestations of above-the ground plant parts start with the appearance of crawlers (the first- instar nymphs) on the underside of the leaves on terminal shoots, stems and other plant parts. Heavy mealybug attack appears as white, waxy masses of mealybugs on stems, nuts and along the veins on the underside of leaves. Heavy infestations usually result in coating of adjacent stems, leaves and nuts with honeydew and sooty mould. Severely infested plants may wilt due to sap depletion; leaves turn yellow, gradually dry and ultimately fall off. Feeding on nuts results in discoloured, bumpy, and scarred nuts, with low market value, or unacceptable for the fresh fruit market. What to do:

|

| Termites (Coptotermes formosanus) Termites can be a serious problem for coconut palms, particularly for young trees in tree nurseries or trees that have just been transplanted into the field. Termites live in the soil in hills, construct tunnel from the hills to the palms and feed on all parts of young coconut palms. Damage occurs mainly during the dry season. Many plants have a repellent or even insecticidal effect on termites and can be applied as spray directly against termites or as barrier around the trunk of coconut palms:

Euphorbia sp.: "In Tanzania, especially in Dar es Salaam and coast regions, farmers plant with each seedling 2 or 3 sticks of Euphorbia sp. to protect the young palms from termite attack. On nurseries the Euphorbia plants can be planted around the seedbed to prevent access of termites to the palm seedlings and young palms. When the palms have grown big the euphorbia is simply cut down. The practice is widespread and farmers are convinced that it really does keep termites off the susceptible seedlings (Z. Seguni, MARI personal communication)".

What to do:

|

| Adult coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) The coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) is the most important pest of coconuts in East Africa. A related species of coconut bug, Pseudotheraptus devastans, causes similar damage to coconuts in West Africa. Adult bugs are brown in colour and 1.2 to 1.4 cm long. They lay eggs singly on the flowers or young nuts. Nymphs are red brown to green brown in colour and have long antenna. Adults and nymphs suck on flowers and developing fruits causing flower abortion and early nutfall. The toxic saliva of the bugs causes necrotic sunken lesions (scars) and cracks on the nuts. Attacked young nuts excrete gum. Many of the attacked young nuts fall off. Nuts older than 3 months at the time of attack may not be aborted but remain small and have scars. Yield losses are difficult to assess since many of the nuts (over 70%) fall naturally. Nuts which abort naturally, do not show scars or gummosis. Two bugs per palm can cause considerable damage. Damage is usually less serious in intercropped coconuts. The bugs also feed on cashew, mango, cocoa and guava. The predatory red weaver ant is an efficient natural enemy of the coconut bug. Weaver ants build nests on palms and other trees by joining leaves with silk produced by their larvae. They forage on the canopy chasing away or killing coconut bugs. Palms with weaver ants are usually free of damage by the coconut bug. Good control is achieved when more than 60% palms are occupied by thriving colonies of weaver ants. Unfortunately other ants present in coconut plantations fight weaver ants, and themselves do not protect (or not as effective as weaver ants) the palms against coconut bugs. These ants such as big headed ant (Pheidole megacephala), the crazy ant (Anoplolepis custodiens), and the long legged ant (Anoplolepis longipes) among others, kill or displace weaver ants, as a result palms are severely damaged. These competing or antagonistic ants need to be managed to allow weaver ants to do their beneficial work. What to do:

|

| African rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes monoceros) It is a stout beetle, about 3.5 to 5 cm long, shiny dark brown to black in colour with a curved horn on the head, hence its common name. The adult flies at night to palms and bore into the hearth of the palms spear, chewing and cutting the youngest unopened leaves and the vegetative bud. Attacked leaves continue to develop and unfold showing a characteristic V-shape damage. If the whole growing point is eaten, the palm usually dies, particularly young palms less than four years old. The boreholes are often marked with a bundle of fibres pushed out of the hole by the beetle. This beetle is a serious pest in plantations where field sanitation is neglected. Eggs are laid in rotting plant material, especially dead palm trunks, compost heaps and rubbish dumps. The larvae (grubs) and pupae develop in rotten coconut logs and other decaying material.

What to do:

|

| Coconut mite (Aceria (=Eriophyes) guerreronis) This mite is tiny and difficult to see with the naked eye. When very many mites are together they appear as fine whitish dust. The coconut mite attacks and damages the upper part of the nutlets under the sepals of up to 6 months old nutlets. Attack is severe during the dry season. Attacked nuts may fall or have a scarred husk, which often splits. The nuts of coconuts showing light scarring on the husk are not seriously affected but in heavily scarred nuts there is significant damage to the nuts.

What to do:

|

| Coconut scale (Aspidiotus destructor) A number of scales feed on leaves and fruits of coconut palms. The most damaging is the coconut scale (Aspidiotus destructor). This scale is bright yellow and round (females) or reddish and oval (males) covered with a semitransparent greyish white flat scale. The scale diameter is 1.5 to 2.0 mm. Females are always wingless and remain under their scale their entire life. Adult males have one pair of membranous wings, move about actively in search of females and do not feed during the adult stage. Eggs are protected underneath the scale or shell of the mother insect until they hatch. Upon hatching the young scales leave the maternal scale, take up a position and start feeding. They do not move afterwards. They are found mainly on the undersides of the leaves, but frond stalks, flower clusters and young nuts can also be attacked. A severe infestation of this armoured scale forms a continuous crust over flower spikes, young nuts and the lower surface of leaves. The leaves become yellow and eventually die. The crown dies leading to collapse of the infested plant. Attacks of young nuts cause shrivelling of nuts leading to premature nut falls. Mostly young coconut trees of up to 10-15 years are vulnerable to damage. Scales may infest palms throughout the year, but damage is usually more severe during the dry season. Neglected plantations are particularly susceptible. The coconut scale also attacks many species of fruit trees, such as avocado, breadfruit, mango, guava and papaya. Other major hosts are cocoa, cassava, cotton, oil palm, papaya, rubber, sugarcane and tea. It also attacks a range of ornamental plants including roses.

What to do:

|

| African palm weevils (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) Adults are large weevils (40-55 mm in long), with a long snout and reddish brown in colour, and generally with 2 reddish bands on the thorax. Females lay eggs on wounds of various origins, on the mature stem as well as in the crown. Upon hatching the larvae (grubs) penetrate into the living tissues of the palm, feeding on the shoot and young leaves, where the insect completes its development in about 3 months. The damaged tissues turn necrotic and decay. Sometimes the grubs feed on the growing point killing the palm. Grubs are whitish-yellow, legless, and oval in shape; their head is reddish brown, and is armed with strong mandibles. Fully-grown grubs are 50 to 60 mm long. The pupal stage is passed within a cocoon of vegetal debris made by the grub at the end of its development. The African palm weevil usually damages young palms, yet may also, in exceptional cases, cause damage to mature crops.

The primary means of control for African palm weevil is preventative, using cultural and sanitary methods.

What to do:

|

Information on pests and diseases

Biological methods of plant protection.

In a balanced cultivation system, which includes middle and bottom crops, as well as nitrogen-fixing green manuring plants (legumes), diseases and pests requiring some form of control measures will rarely occur, especially when enough birds are present on the plantation. These are often present in multi-level cultivation systems (see diversification strategies above).Most of the problems concerning disease and pests have the following causes:

- Cultivation in a monoculture, or with too few different varieties.

- Too little distance between species that grow to the same height; failure to trim agroforestry systems.

- Degenerated or poor soil, lacking organic material.

- Unsuitable sites (water-logging, too dry, soil not deep enough for roots).

In most cases, the most effective cure is to alter the entire system of cultivation. If a system is not yet in a state of ecological equilibrium, bud rot or heart rot, caused by Phytophthora palmivora, can occur in all of the producing regions - where it is widely spread. In cases of heavy infestation with Phytophtora palmivora, harvest-losses can be lessened by using Bordeaux mixture, or any other copper-rich spraying preparations, which are permitted in organic farming systems. These measures should only be undertaken in cases of emergency. In less severe cases, removing any infested plants from the plantation will result in the infection being limited. Amongst the young trees in tree nurseries, an attack of termites may occur. The termites can be effectively combated by pouring a thin layer of sand from the soil over the exposed parts of the buried nuts. Young coconut palms are also susceptible to the rhinoceros beetle and coconut caterpillars. Pheromone traps have been successfully utilised in Sri Lanka against the rhinoceros beetle. In emergency cases, butterfly caterpillars can be regulated with Bacillus thuringiensis (Bf).The trunks of young seedlings are often protected against pests by painting them with tar. This is not allowed an organic plantations, and the black covering also causes the plants to heat up unnecessarily. An alternative is to paint the trees with a mixture of sulphur, soil and lime, (1 : 2 : 1) added together with water to make a thick paste. If necessary, the paste may need to be renewed, as rain will wash it off.Coconut red weevil and Rhinocerus beetle only usually damage young palms, yet may also, in exceptional cases, cause damage to mature crops. In acute cases, they can be combated by closing the larvae tunnels, and with pheromone traps.In coconut palm monocultures, rodents, and especially rats, can develop into a serious epidemic which is then difficult to bring under control again. Metal plates affixed to the trunks will effectively stop them from climbing up the trees.

Examples of Coconut Diseases and Organic Control Methods

| Lethal bole rot (Marasmiellus cocophilus) In East Africa, Marasmiellus cocophilus causes death of palms up to 8 years old, seedlings being highly susceptible on transplanting to the field. Root infections occur, leading to decay of basal tissues and finally a rot of the spear leaf. On older palms, the first symptoms are a general wilt of the fronds, which remain as a 'skirt' around the trunk. The spear leaf dies and a foul-smelling soft rot develops at the base of the leaves. A dry, reddish-brown rot with a yellow margin is typically present at the base of the bole. Cavities within these areas of rot are lined with mycelium (fungal growth) in young palms, 2-4 years old, but rare in 4-6-year-old palms, and absent in mature palms. Fungal bodies (like small mushrooms) commonly occur on exposed roots, leaf bases of seedlings, exposed tops of seed nuts and on the soil surface around holes (growing from coconut debris) where diseased palms had been removed 2 years previously. On average, there is only about 8 weeks from the time of onset of symptoms till the death of the palm; this interval depends on the extent of fungal decay in the bole. Spread occurs through soil, root contact between palms, infected coconut debris and probably by airborne basidiospores (fungal spores). Infection also occurs via wounds.

What to do:

|

| Lethal yellowing (Phytoplasma) Symptoms include necrosis of inflorescences, yellowing of leaves and premature shedding of all fruit (nut fall) regardless of their developmental stage. Aborted nuts often develop a brown-black calyx-end rot reducing seed viability. Premature nut fall is accompanied or followed by inflorescence necrosis. This symptom is most readily observed as newly mature inflorescences emerge from the spathe. Normally light yellow to creamy white in colour; affected inflorescences are instead partially blackened (necrotic) usually at the tips of flower spikelets. As disease progresses, additional emergent or unemerged inflorescences show more extensive necrosis and may be totally discoloured. Such symptom intensification results in the death of most male flowers and an associated lack of fruit set. Yellowing of the leaves usually starts once necrosis has developed on two or more inflorescences and discolouration is more rapid than that associated with normal leaf senescence. Yellowing begins with the older (lowermost) leaves and progresses upward to involve the entire crown. Yellowed leaves turn brown, desiccate and die. In some cases, the advent of this symptom is seen as a single yellow leaf (flag leaf) in the mid-crown. Affected leaves often hang down forming a skirt around the trunk for several days before falling. A putrid basal soft rot of the newly emerged spear (youngest leaf) occurs once foliar yellowing is advanced. Spear leaf collapse and rot of the apical meristem invariably precedes death of the palm at which point the crown topples away leaving a bare trunk. Infected palms usually die within 3 to 6 months after the appearance of the first symptoms. Lethal yellowing symptomatology may be complicated by other factors. For example, non-bearing palms lack fruit and flower symptoms. Foliar discolouration also varies markedly among coconut ecotypes and hybrids. For most tall-type coconut palms, leaves turn a golden yellow before dying whereas on dwarf ecotypes leaves generally turn reddish to greyish-brown. Phytoplasmas are transmitted in a persistent (circulative-propagative) manner primarily by insect vectors belonging to the families Cicadelloidae (leafhoppers) and Fulgoroidae (planthoppers).

What to do:

|

| Bud rot (Phytophthora palmivora) Bud rot (also called heart rot) caused by the fungus Phytophthora palmivora has an extensive host range of more than 200 plant species and it is widespread in the tropics including tropical Africa. The fungus enters into the plant by infecting tender host tissues (leaves, buds or young nuts). Affected leaves turn yellow and later brown.

The heart leaf becomes chlorotic, wilts and collapses. The disease may spread to older, adjacent leaves and spathes, producing a dead centre with a fringe of living leaves. Light brown to yellow, oily, sunken lesions may be found on leaf bases, stipules or pinnae. Internally, the tissues beneath the bud are discoloured pink to purple with a dark brown border. Affected leaves progressively drop. Infected nuts show brown to black necrotic areas with a yellow border developing on the surface; internally, they have a mottled appearance. Young nuts are highly susceptible and fail to mature, they then fall off the tree; older infected nuts ripen normally.

What to do:

|

Contact Information

- Industrial Crop Research Institute, Mtwapa (icri@kalro.org; +254 (20) 2024751)

- Food Crop research Institute, Muguga Sub Centre (fcri@kalro.org +254 (20) 3509161)

References and Information Source Links

1. Anon. (1990). Hypothesizing about palm weevil and palm rhinoceros beetle larvae as traditional cuisine, tropical waste recycling, and pest and disease control on coconut and other palms... can they be integrated? The Food Insects Newsletter, 3(2):1-4.

2. Bohlen, E. (1973). Crop pests in Tanzania and their control. Federal Agency for Economic Cooperation bfe. Verlag Paul Parey. ISBN: 3-489-64826-9.

3. CAB International (2006). Crop Protection Compendium, 2006 Edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

4. Cocos nucifera L. in GBIF Secretariat (2021). GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-12-22.

5. Field Crops technical Handbook (2002). Agricultural Information Centre, Nairobi Kenya

6. Griesbach, J. (1992). A Guide to Propagation and Cultivation of Fruit Trees in Kenya. Schriftenreihe de GTZ, No. 230. Published by Technical Cooperation- Federal Republic of Germany (GTZ). ISBN: 3 88085 482 3

7. Hill, D. (1983). Agricultural insect pests of the tropics and their control. 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0-521-24638-5.

8. Integration of Tree Crops into Farming Systems Project & Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Kenya (2000). Tree Crop Propagation and Management - A Farmer Trainer Training Manual.

9. Kessing, J.L.M., Mau, R.F.L. (2007). Crop Knowledge Master. Coconut scales Aspidiotus destructor. Updated by: J.M. Diez April 2007. www.extento.hawaii.edu

10. Naturland e.V. (2000). Organic Farming in the Tropics and Subtropics: Coco palms. Available also online http://www.naturland.de

11. Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

12. Orwa C, A Mutua, Kindt R, Jamnadass R, S Anthony. 2009 Agroforestree Database:a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0 (http://www.worldagroforestry.org/sites/treedbs/treedatabases.asp)

13. Van Mele, P., Cuc, N. T.T. (2007). Ants as friends. Improving your tree crops with weaver ants. (2nd Edition). Africa Rice Center (WARDA), Cotonou, Benin and CABI, Egham, U.K. 72 pp. ISBN: 92-913-3116.

14. Varela, A. M. (1993). Studies on the distribution and importance of the coconut mite Eriophyes guerreronis Keifer, as a pest of coconut palms in Tanzania. Internal report. National Coconut Development Programme (NCDP).

15. Van der Vossen, H.A.M. & Chipungahelo, G.S.E., 2007. Cocos nucifera L. [Internet] Record from PROTA4U. van der Vossen, H.A.M. & Mkamilo, G.S. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. <http://www.prota4u.org/search.asp>. Accessed 14 December 2021.

16. Varela, A. M. (1997). Establishment of Oecophylla longinoda Latreille (Formicidae), a predator of the coconut bug Pseudotheraptus wayi Brown (Coreid) in new areas in Tanzania. Proceedings of the International Cashew and Coconut Conference, Dar es Salaam. Pp 442-446.

17. Way, M. J., Khoo, K. C. (1992). Role of ants in pest management. Annual Review of Entomology. Vol 37: 479-503.

Review Process

Dr. Patrick Maundu, James Kioko, Charei Munene and Monique Hunziker, June 2024