|

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporiodes) The most serious and widespread fungus is anthracnose. Anthracnose initially appears as small black spots. On leaves, the spots can grow to form an irregular patch. On young fruit, pin-sized, brown or black, sunken spots develop. Sometimes, a "tear stain" pattern develops on fruit. It is an important problem after harvesting the fruit, especially during transport and storage, where fruit can develop round, blackish sunken spots. The fungus is spread by rain splash and survives from season to season on dead leaves and twigs. Rainy weather during blooming and early fruit set will favour the development of anthracnose.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mango aphid (Toxoptera odinae) It is small (1.1 to 2.5 mm long), brown, black or reddish brown aphid covered with a light powdery dusting. Aphids live in clusters sucking sap on the underside of young leaves, on petioles, young branches and fruit. Their feeding causes slight rolling, or twisting of the leaf midrib. Sooty mould growing on honeydew produced by the aphids may cover leaves, twigs and fruit. Coating of the fruit with honeydew and sooty mould reduces its market value.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Bacterial black spot (Xanthomonas campestris pv. mangiferaeindicae) Bacterial black spot is rain related and is spread through rain splash within an orchard. Long-distance spread is by infected planting material. Important factors in infection are very small wounds that are easily caused by wind and wet weather. On leaves, spots are angular, dark, shiny in appearance and delimited by veins. Fruit spots start off as water soaked and then become raised and black. Later they crack open in the centre in form of a star. In wet weather, these spots exude gum. Fruit becomes more susceptible with age.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Bugs Several species of bugs feed on mangoes. Both adults and nymphs (young stages) feed inserting their needle-like mouthparts in young tissue, causing dieback and tip wilting. Other feed on the fruit, causing fruit fall and fruit deformation.

Coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) It feed on fruits. Damaged young fruits show dark brown or grey indentations on the skin and normally drop. Bug feeding on mature fruit causes sunken lesions. The coconut bug is reddish brown, about 1.5 cm long. Eggs are laid scattered over the fruit, small twigs, flowers and blossom stems. The young bugs are light brown with long thick antenna.

Tip wilters (Anoplocnemis curvipes) They are large (about 2.5 cm long) bugs, and dark brown in colour. The hind legs of the male are enlarged. Both young and adult bugs feed on young flush, on the mid-vein of young leaves, or on flower stalks, causing wilting and death of new growth. Heliopeltis bugs, also known as mosquito bugs are about 7-10 mm long and have slender bodies and long legs and antenna. Adults and young bugs (nymphs) feed on fruit and young shoots. Feeding on fruit causes dark lesions with a brown dark centre. Young shoots die back, resulting in vigorous secondary branching. Bugs are difficult to control since they usually feed on a wide range of crops and are very mobile.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mango fruit flies (Ceratitis spp./ Bactrocera invadens) Fruit flies lay eggs under the skin of mature green and ripening fruit. Some fruit flies such as Bactrocera invadens, a new species recently introduced into East Africa, also lay eggs on small fruit. The eggs hatch into whitish maggots within 1 to 2 days. The maggots feed on the fruit flesh and the fruit starts to rot. After 4 to 17 days, the maggots leave the fruit, making holes in the skin. Adult fruit flies are about 4-7 mm long. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Helopeltis bugs (Helopeltis schoutedeni and H. anacardii) Helopeltis bugs, also known as mosquito bugs or mirid bugs are slender, delicate insects, about 7- 10 mm long with long legs and antennae, the antenna being nearly twice as long as the body. The females are red and the males brown to yellowish red. They lay eggs inserted into the soft tissue near the tips of flowering or vegetative shoots. Nymphs (immature bugs) are yellowish in colour. Both adults and nymphs feed on young leaves, young vegetative and flowering shoots, and developing fruits.

Attacked leaves are deformed and show angular lesions, particularly along the veins, which may drop off, so that the leaves appear as if attacked by biting insects. Feeding on the stalks of the tender shoots causes elongated green lesions, sometimes accompanied by exudation of gum. Severely damaged shoots die back due to the effect of bug saliva in combination with fungi, which enter the plant tissue through the feeding lesions and the subsequent development of numerous auxiliary buds causes a bunched terminal growth known as 'witches broom'. In case of serious infestations the trees may appear as if scorched by fire. Bug feeding on developing fruits causes brown sunken spots. The growth of trees is seriously retarded and fruit formation is reduced.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Malformation (Fusarium subglutinans) The fungus produces compounds that have hormonal effect on the plant. The fungus is easily spread by grafting and infected nursery trees. In the orchard the disease spreads slowly despite of masses of spores produced on the panicles. Symptoms consist of affected flowers taking on, to a greater or lesser extent, the appearance of a cauliflower head. The axes of the panicles are shorter and thicker than normal, branch more often, and a profusion of enlarged flowers is produced. The affected panicles retain their green colour, are sterile and produce no fruits. In the nursery, vegetative malformation can occur. Eriophid mites are believed to be vectors of the disease and their damage symptoms are similar to those caused by F. subglutinans. Symptoms consist of buds producing short shoots and small brittle leaves creating a compact "witches broom" appearance.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mango gall flies (Erosomyia mangifera) It is a small midge about 1 to 2 mm long with long legs and antenna. The flies lay eggs on young leaves. Eggs hatch into maggots that bore into the leaf tissue to feed. Their feeding induces formation of small galls, which look like pimples on the leaves. Mature maggot leaves the galls and drop to the soil to pupate, leaving small holes on the leaves. These holes may serve as entrance for fungal infections. Leaves may be covered with galls and the surrounding tissue may die. Heavy infestation may lead to premature leaf drop.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mango leaf coating mite (Cisaberoptus kenyae) The mango leafcoating mite is tiny (about 0.2 mm), light coloured and cigar shaped. It cannot be seen with the naked eye. The mites leave in groups under a white coating on the upper leaf surface. The white coating can be easily rubbed off by hand. Leaves covered with the white coating tend to turn yellow and drop prematurely. In general, the coating has minimal effect on fruit yield.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mango seed weevil (Sternochetus mangiferae) It feeds on mango leaves, tender shoots or flower buds. Female weevils lay one egg on the young fruit leaving a small, dark mark on the fruit skin. The larvae burrow through the flesh into the seed and destroy it. The larva develops and grows in the mango seed. When the larva has grown up to an adult beetle, it tunnels through the flesh and leaves a hole in the fruit skin. The tunnel gets hard and the fruit cannot be sold anymore.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mealybugs (Rastrococcus spp.) Mealybugs are small, flat, soft bodied insects covered with a distinctive segmentation. Their body is covered with a white woolly secretion. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruits. Seriously attacked leaves turn yellow and eventually dry. This can lead to shedding of leaves, inflorescences, and young fruit. Mealybugs excrete honeydew on which sooty mould developed. Heavy coating with honeydew blackens the leaves, branches and fruit. This reduces photosynthesis, can cause leaf drop and affect the market value of the fruit.

A wide range of natural enemies attacks mealybugs. The most important are ladybird beetles, hover flies, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. These natural enemies usually control mealybugs. However, mealybugs can cause economic damage to mango when natural enemies are disturbed (for instance by ants feeding on honeydew produced by mealybugs or other insects) or killed by broad-spectrum pesticides, or when mealybugs are introduced to new areas, where there are no efficient natural enemies.

The latter is the case of two serious mealybug pests on mangoes in Africa: Rastrococcus invadens in West and Central Africa and Rastrococcus iceryoides in East Africa. These mealybugs, of Asian origin, were introduced into Africa, where they developed into serious pests since the natural enemies present were not able to control them. They cause shedding of leaves, inflorescences and young fruits. In addition, sooty moulds growing on honeydews excreted by the insects render the fruits unmarketable and the trees unsuitable for shading. They cause direct damage to fruits leading to 40 to 80% losses depending on locality, variety and season. Rastrococcus invadens was brought under control in West and Central Africa by two parasitic wasps (Gyranusoidea tebygi and Anagyrus mangicola) introduced from India (Neuenschwander, 2003).

Rastrococcus iceryoides is a major pest of mango in East Africa, mainly Tanzania and coastal Kenya. Although several natural enemies are known to attack this mealybug in its aboriginal home of southern Asia (Tandon and Lal, 1978; CABI, 2000), none have been introduced so far into Africa (ICIPE). Insecticides do not generally provide adequate control of mealybugs owing to their wax coating. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Powdery mildew (Oidium mangifera) It appears as a white, powdery growth on leaves, flowers and young fruit. Infected leaves curl and flowers fail to open and drop from the tree without forming a fruit. The disease is spread by wind and can spread very rapidly. It is more prevalent in dry weather when humidity is high and nights are cool. The fungus survives from season to season in dormant buds. The flowering stage is the most critical stage for infection.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Scales Scales are small (1 to 7 mm long), generally immobile insects, varying in colour and shape according to the species. Female scales have neither wings nor legs. They resemble small shells glued to the plant. Females lay eggs under their scale. Once hatched, the tiny scales (known as crawlers) emerged from under the protective scale. They move in search of a feeding site and do not move afterwards. They suck sap on all above the ground plant parts.

There are two main groups of scales on mangoes: soft and armoured scales. Soft scales excrete honeydew. The most common soft scales on mangoes are soft green scales (Coccus viridis), brown soft scales (Coccus hesperidum), and wax scales (Ceroplastes spp.). The most important armoured scale on mango is the mango white scale (Aulacaspis tubercularis). The body of this scale is reddish brown. Females are covered with a white round shell, while males have a small rectangular shell with two groves. Feeding by scales may cause yellowing of leaves followed by leaf drop, poor growth, dieback of branches, fruit drop, and blemishes on fruits. Heavily infested young trees may die. In addition, soft scales excrete honeydew, causing growth of sooty mould. In heavy infestations fruits and leaves are heavily coated with sooty mould, turning black. This reduces photosynthetic capacity. Fruits contaminated with sooty mould loose market value. Ants are usually associated with soft scales. They feed on the honeydew excreted by soft scales, preventing a build-up in sooty moulds, but also protecting the scales from natural enemies. Armoured scales do not excrete honeydew.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Spider mites (Tetranychus spp.) They can damage maize from the seedling stage to maturity. The presence of small, faint yellow blotches on the lower leaves is an indication of spider mite injury. As the colonies of mites increase in size they cause the lower leaves to become dry. The mites then migrate to the upper leaves. In Africa several species of spider mites have been reported on maize (mainly Tetranychus spp. and Olygonichus spp.). In Kenya, they are occasionally found on maize, but usually they are not of economic importance.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Stem-end rot (Dothiorella dominicana, Botryodiplodia theobromae, Phomopsis mangiferae) Symptoms consist of a dark-brown, firm decay starting at the stem-end of the fruit and developing rapidly to involve the whole fruit. The fungi survive on dead twigs and branches where they produce large numbers of spores. During wet weather, these spores are spread to adjacent fruits where infection occurs. The rot generally does not develop until the fruits begin to ripen. Chemical sprays are neither recommended nor necessary.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Bark eating termites They are generally associated with old mango trees. They may damage branches and other parts by tunnelling the wood, but usually are not of economic importance. Sickly, injured plants are more likely to be damaged than healthy, vigorous plants.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Red banded thrips (Selenothrips rubrocinctus) The adult of the red banded thrips is reported as a pest of mangoes in Kenya (AIC, 2003). Adult thrips are dark brown, about 1 mm long. Immature thrips (nymphs) are yellow with a bright red band around the base of the abdomen. Nymphs and adults feed together, normally on the underside of the leaves. Attacked leaves become dark stained and rusty in appearance with small shiny black excreta present. Leaf edges are curled. Several other species of thrips are found on mango flowers. However, not all of them are pests. Their role varies according to the species. Some species are present in large numbers in mango flowers, but there is no evidence of damage or crop loss. Some thrips species are considered important pollinators. Other species of thrips attack the mango fruit. Thrips feeding on the fruit surface causes a rough, greyish white discolouration.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Whiteflies and black flies (Aleurocanthus woglumi) Whiteflies and black flies suck sap from leaves and may weaken the plants when numbers are high. They produce large amount of honeydew where sooty mould develops. High numbers of these insects can almost blacken trees, reducing photosynthesis and may cause leaf drop debilitating the tree. Adults are small (1-3 mm long), with 2 pairs of wings that are held roof-like over the body. They resemble very small moths. |

|

|

What to do:

|

Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Mango in Africa.Updated July 2019. Source FAOSTAT

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

The Mango fruit is one of the most important tropical fruits. It is native to the Indian Monsoon region and has been cultivated for the last 4000 years. It was introduced to East Africa in the 14th century. Mango has now become an important domestic and export crop in Kenya and Tanzania.

Mango has many uses: ripened fruits are eaten fresh and used to make juice or marmalade. They can also be dried and made into candy. All remains from the fruits can be used to feed animals. The young leaves for example are a very good cattle feed.

Cultivars

A wide range of mango cultivars is grown in Kenya. Local varieties include:

Apple, Batawi, Boribo, Dodo, Kiarabu, Kiimji, Kitovu, Mayai, Ngowe, Peach, Sabre and Shikio Punda. Among these, Apple and Ngowe are in high demand for local and export markets, particularly in the Middle East. Apple, Haden, Keitt, Kent, Ngowe and Tommy Atkins are important cultivars for the export markets.

Nutritive Value per 100 g of edible Portion

| Raw or Cooked Mango | Food Energy (Calories / %Daily Value*) |

Carbohydrates (g / %DV) |

Fat (g / %DV) |

Protein (g / %DV) |

Calcium (g / %DV) |

Phosphorus (mg / %DV) |

Iron (mg / %DV) |

Potassium (mg / %DV) |

Vitamin A (I.U) |

Vitamin C (I.U) |

Vitamin B 6 (I.U) |

Vitamin B 12 (I.U) |

Thiamine (mg / %DV) |

Riboflavin (mg / %DV) |

Ash (g / %DV) |

| Mango raw | 65.0 / 3% | 17.0 / 6% | 0.3 / 0% | 0.5 / 1% | 10.0 / 1% | 11.0 / 1% | 0.1 / 1% | 156 / 4% | 765 IU / 15% | 27.7 / 46% | 0.1 / 7% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 4% | 0.1 / 3% | 0.5 |

*Percent Daily Values (DV) are based on a 2000 calorie diet. Your daily values may be higher or lower, depending on your calorie needs.

Climate conditions, soil and water management

Mango grows best in tropical summer rain regions, at temperatures between 24°C and 28°C. Once a mango tree is well established, it is very resistant to drought. Mango needs a dry period or cooler temperatures to start blossoming and produce fruits. Rainfall during flowering seriously affects fruit setting. In the tropical regions that do not vary in rainfall or temperature, the trees will not produce any fruits. Mangoes grow well below an altitude of 1000 m. Above 1200 m production is often poor, but some cultivars such as "Sabre" and "Harris" are reported to yield well at up to 1800 m.

Mango will grow on a rainfall as little as 650 mm per year, but do better on higher rainfall of around 1500 mm.

Mango grow in most soils if they are well drained. Ideal for good growth is a deep (at least three m), fertile soil. Avoid poor, shallow, rocky and alkaline soils. A pH of 5.5 to 7.5 is desirable. Young trees should be irrigated as soon as the dry season starts. Older trees need a dry period of at least three months to start flowering. When the fruit is developing, it is very important to water the plant regularly. In Kenya, the major production season is December to March.

Propagation and planting

Mango is propagated both vegetatively and by seed. Nurserymen and farmers should be aware that not all cultivars propagated by seed will produce seedlings true to the parent tree. Two groups can be differentiated:

- Polyembryonic cultivars from seed are generally true to the parent tree and they include local cultivars like "Batawi", "Boribo", "Dodo", "Ngowe", "Peach" and "Sabre". In addition to the sexual seedling (which has to be culled out), seeds of these cultivars produce up to 5 nucellar embryos, each genetically identical to the parent tree.

- Monoembryonic cultivars like "Haden", "Kent", "Tommy Atkins" and "Van Dyke" can only prppagate true-to-type by using vegetative methods. Vegetative propagation has many advantages (e.g. early bearing, smaller trees, etc) and should be encouraged. For this purpose, rootstock seedlings must be made available. "Dodo", "Peach" and "Sabre" are commonly used rootstocks in Kenya.

Mango seeds quickly loose their viability. Use healthy, fresh seeds from well-grown, mature trees. Wash the seeds and dry them in the shade for a few days. Sow them at a spacing of 15 x 30 cm and five cm deep. Place them on their sides; the most prominently curved edge upwards, so that they produce a straight stem. To speed up germination, the hard husk can be removed before sowing. The best place to cultivate seedlings is in half-shadow. Seeds will sprout in 1 to 2 weeks and, as soon as the first flush of growth hardens (about 4 weeks later and about 10 cm high), they are transplanted into containers (about 18 x 24 cm). Plants are ready for grafting when they have reached pencil-thickness at about 20 cm above soil level. Cleft graft with scion of improved cultivars. Sources of scions of improved cultivars in Kenya include Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) (Embu, Mtwapa, Thika), prison farms or any farm with the desired cultivars. Shade the grafted plants and water frequently. Grafted seedlings are ready for transplanting about 4 months after grafting.

Select the site for the orchard carefully. Deep soil cultivation by ploughing is recommended. Clear the field of trees, bushes and weeds. Transplanting should be done at the beginning of the rains. The planting hole should be 60 x 60 cm and 100 cm deep. Under dry conditions, the hole should be bigger (about 90 x 90 cm and 100 cm deep). The spacing is 9 x 9 to 14 x 14 m between trees depending on variety and growth habit of the mango variety chosen. Mix a minimum of two buckets of good compost and a handful of Mijingu rock phosphate with the dug out soil, before returning the soil to the hole along with the young mango plant. Firm the soil around the plant. Water well and mulch. Irrigation should only be necessary to see the young tree through the first year.

Husbandry

Keep the area directly under the tree canopy free from weeds. During the first five years, intercropping with annual crops is recommended to maximise income until an economical mango yield is achieved. In young plantations mulching around the tree helps to suppress weeds and to retain soil moisture. Mango trees normally need pruning in order to shape young trees. Smoking of mango trees, apart from controlling pests also induces good flowering.

Formative pruning is done in the first years of the young tree to guide the tree into the desired shape. In the first year, cap the seedling at 1 m height in order to produce a spreading framework of branches. In the second year, prune to leave 4 to 5 well spaced branches to be the future main branches. Benefits from pruning:

- Fruit is produced on the outside of parts of the tree

- Fruit hold to maturity on the trees

- Open tree structure allows for easy harvesting

- Tree produces larger fruits

- Crops can be grown under the trees

- Tree benefits from natural conditions of sun and wind movement. This helps in reducing relative humidity within the canopy and also creating environment less conducive to disease development.

- It controls tree height and prevents excessive spreading of limbs.

Structural pruning should be done after fruit harvest: The canopy should be at least one m above the ground. Remove all dead branches and all sucker branches from the main structural branches. Prune canopy to allow sunlight to penetrate and reach the ground under the tree.

Improve fruit production by:

- Keeping the orchard area clean

- Removing all ripe fruit and weeds from around the tree

- Removing 1/3 of fruit after fruit set to get better size of remaining fruit.

Mango trees are susceptible to wind damage. Therefore, they should be protected from strong winds by windbreaks on the upwind side of prevailing winds.

Weeding

Clear excessive vegetation regularly from beneath the trees and use as mulch.

|

| Mango fruits and farmers inspecting a mango tree |

|

© A. M. Varela & A.A. Seif, icipe

|

Harvesting

Flowering usually begins after a period of dormancy due to cool or dry weather. Smallholder mango farmers usually induce flowering with smoke.

A mango plantation will supply its first commercially marketable amount of fruit around 4 to 5 years after being planted, and are in good production after eight years reaching full maturity at some 20 years of age. One tree should produce 200 to 500 fruits per year and varieties like "Dodo" and "Boribo" can produce 1000 fruits per year. Most varieties show biennial tendencies in production and a poor harvest may follow a good one. Selection should be based on varieties showing annual bearing tendencies.

Harvest mango fruit at the mature-green stage, when they are hard and green. A mature fruit has well-developed "cheeks". Pick fruit by hand. Clip them off with a long stalk of about 2 to 3 cm and pack the fruit in a single layer with the stalks facing downwards in the box or crate. It is important that the latex dripping from the stalk drops onto an absorbent material (for example tissue paper placed at the bottom of the container). Although mature mangoes ripen fairly rapidly, they have a poor tolerance to temperatures below 10°C, especially when freshly picked. Ripe fruits can, however, be stored as low as 7 to 8° C without developing chilling injury.

Yield

15 tons/ha per year can be achieved from the 7th year onwards if proper husbandry is followed.

Post-harvest treatment

Hot water treatment (HWT) is an effective post-harvest treatment method for mango. Dipping newly harvested fruits into hot water minimises fruit fly damage and anthracnose. The fruit is perishable and should be marketed as quickly as possible.

For more information on hot water treatment click here.

Mango hygiene by smoking

Mango smoking reduces insect population drastically and improves fruit setting.

Smoke pots with holes in the bottom for air intake, containing wood shavings or sawdust with a topping of aromatic herbs (lemongrass etc) are hung at strategic places within the mango tree and the sawdust lit to produce a good amount of smoke which chases insects away from the tree.

|

| Mango hygeine by smoking |

|

(c) A. M. Varela & A.A. Seif, icipe

|

Another option is to place dry grass on the ground below the tree in a position where the wind can blow maximum smoke into the top of the tree, cover it with green aromatic leaves like lantana etc and lit the grass to produce smoke.

Smoking of mango trees is reported both by Kenya Institute of Organic Farming (KIOF) and Meru Herbs Farmers, Kenya to be very effective in insect control.

Smoking also induces flowering in mango trees.

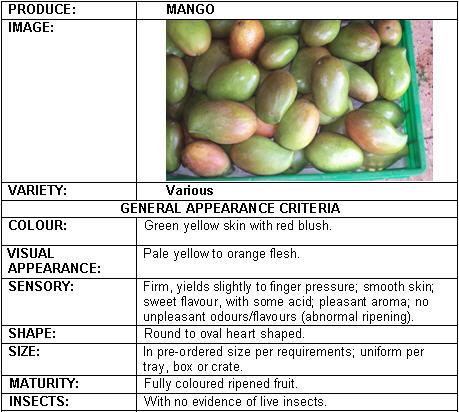

Fresh Quality Specifications for the Market in Kenya

|

|

© S. Kahumbu, Kenya

|

Information on Pests

Biological methods of plant protection

The worst pests for mangoes include fruit flies, cotton scales, mealybugs, cicadas and black flies (create honey dew). They can cause a lot of damage. Yet they all have natural enemies, such as e.g. ladybird larvae, wasps, spiders and parasitic fungi (e.g. with cicadas and black flies).

An ecological plantation with a variety of crops and a sufficient amount of vegetation cover will provide enough natural enemies to combat the pests that measures against them unnecessary. Cicadas are averse to open, well ventilated soil, also drain the soil well to avoid wet patches.

In emergencies, the following methods should help:

Scale insects can be regulated with a 'winter-spraying', i.e. with paraffin oil (white oil) shortly before the larvae hatch from their eggs. The paraffin oil is sprayed on as a 3 % water emulsion.

Plant spraying mixtures made of stinging nettles or neem can be used against cicadas. The worst damage occurs during blossoming, so the plantation should be checked regularly around this time in order to make up the brew and spray it early enough.

Mealybugs lay their eggs on the ground next to the trunk. By wrapping smooth plastic bands around the trunk, the larvae can be prevented from infesting too large an area. Should they infest the tree, a solution of 1% soft soap (potassium soap) is quite effective.

Black fly can be kept under control by useful insects. A variety of prospatella species can be of use here. This requires a good functioning control system, because the useful larvae need to be made available for release in time. Where this is not possible, spraying white oil shortly before the pests hatch, as such as with scale insects can be sufficient.

Examples of Mango Pests and Organic Control Methods

| Mango fruit flies (Ceratitis spp./ Bactrocera invadens) Fruit flies lay eggs under the skin of mature green and ripening fruit. Some fruit flies such as Bactrocera invadens, a new species recently introduced into East Africa, also lay eggs on small fruit. The eggs hatch into whitish maggots within 1 to 2 days. The maggots feed on the fruit flesh and the fruit starts to rot. After 4 to 17 days, the maggots leave the fruit, making holes in the skin. Adult fruit flies are about 4-7 mm long. What to do:

|

| Mango gall flies (Erosomyia mangifera) It is a small midge about 1 to 2 mm long with long legs and antenna. The flies lay eggs on young leaves. Eggs hatch into maggots that bore into the leaf tissue to feed. Their feeding induces formation of small galls, which look like pimples on the leaves. Mature maggot leaves the galls and drop to the soil to pupate, leaving small holes on the leaves. These holes may serve as entrance for fungal infections. Leaves may be covered with galls and the surrounding tissue may die. Heavy infestation may lead to premature leaf drop.

What to do:

|

| Whiteflies and black flies (Aleurocanthus woglumi) Whiteflies and black flies suck sap from leaves and may weaken the plants when numbers are high. They produce large amount of honeydew where sooty mould develops. High numbers of these insects can almost blacken trees, reducing photosynthesis and may cause leaf drop debilitating the tree. Adults are small (1-3 mm long), with 2 pairs of wings that are held roof-like over the body. They resemble very small moths. What to do:

|

| Mango aphid (Toxoptera odinae) It is small (1.1 to 2.5 mm long), brown, black or reddish brown aphid covered with a light powdery dusting. Aphids live in clusters sucking sap on the underside of young leaves, on petioles, young branches and fruit. Their feeding causes slight rolling, or twisting of the leaf midrib. Sooty mould growing on honeydew produced by the aphids may cover leaves, twigs and fruit. Coating of the fruit with honeydew and sooty mould reduces its market value.

What to do:

|

| Mango seed weevil (Sternochetus mangiferae) It feeds on mango leaves, tender shoots or flower buds. Female weevils lay one egg on the young fruit leaving a small, dark mark on the fruit skin. The larvae burrow through the flesh into the seed and destroy it. The larva develops and grows in the mango seed. When the larva has grown up to an adult beetle, it tunnels through the flesh and leaves a hole in the fruit skin. The tunnel gets hard and the fruit cannot be sold anymore.

What to do:

|

| Mealybugs are small, flat, soft bodied insects covered with a distinctive segmentation. Their body is covered with a white woolly secretion. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruits. Seriously attacked leaves turn yellow and eventually dry. This can lead to shedding of leaves, inflorescences, and young fruit. Mealybugs excrete honeydew on which sooty mould developed. Heavy coating with honeydew blackens the leaves, branches and fruit. This reduces photosynthesis, can cause leaf drop and affect the market value of the fruit.

A wide range of natural enemies attacks mealybugs. The most important are ladybird beetles, hover flies, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. These natural enemies usually control mealybugs. However, mealybugs can cause economic damage to mango when natural enemies are disturbed (for instance by ants feeding on honeydew produced by mealybugs or other insects) or killed by broad-spectrum pesticides, or when mealybugs are introduced to new areas, where there are no efficient natural enemies.

The latter is the case of two serious mealybug pests on mangoes in Africa: Rastrococcus invadens in West and Central Africa and Rastrococcus iceryoides in East Africa. These mealybugs, of Asian origin, were introduced into Africa, where they developed into serious pests since the natural enemies present were not able to control them. They cause shedding of leaves, inflorescences and young fruits. In addition, sooty moulds growing on honeydews excreted by the insects render the fruits unmarketable and the trees unsuitable for shading. They cause direct damage to fruits leading to 40 to 80% losses depending on locality, variety and season. Rastrococcus invadens was brought under control in West and Central Africa by two parasitic wasps (Gyranusoidea tebygi and Anagyrus mangicola) introduced from India (Neuenschwander, 2003).

Rastrococcus iceryoides is a major pest of mango in East Africa, mainly Tanzania and coastal Kenya. Although several natural enemies are known to attack this mealybug in its aboriginal home of southern Asia (Tandon and Lal, 1978; CABI, 2000), none have been introduced so far into Africa (ICIPE). Insecticides do not generally provide adequate control of mealybugs owing to their wax coating. What to do:

|

| Scales are small (1 to 7 mm long), generally immobile insects, varying in colour and shape according to the species. Female scales have neither wings nor legs. They resemble small shells glued to the plant. Females lay eggs under their scale. Once hatched, the tiny scales (known as crawlers) emerged from under the protective scale. They move in search of a feeding site and do not move afterwards. They suck sap on all above the ground plant parts.

There are two main groups of scales on mangoes: soft and armoured scales. Soft scales excrete honeydew. The most common soft scales on mangoes are soft green scales (Coccus viridis), brown soft scales (Coccus hesperidum), and wax scales (Ceroplastes spp.). The most important armoured scale on mango is the mango white scale (Aulacaspis tubercularis). The body of this scale is reddish brown. Females are covered with a white round shell, while males have a small rectangular shell with two groves. Feeding by scales may cause yellowing of leaves followed by leaf drop, poor growth, dieback of branches, fruit drop, and blemishes on fruits. Heavily infested young trees may die. In addition, soft scales excrete honeydew, causing growth of sooty mould. In heavy infestations fruits and leaves are heavily coated with sooty mould, turning black. This reduces photosynthetic capacity. Fruits contaminated with sooty mould loose market value. Ants are usually associated with soft scales. They feed on the honeydew excreted by soft scales, preventing a build-up in sooty moulds, but also protecting the scales from natural enemies. Armoured scales do not excrete honeydew.

What to do:

|

| Several species of bugs feed on mangoes. Both adults and nymphs (young stages) feed inserting their needle-like mouthparts in young tissue, causing dieback and tip wilting. Other feed on the fruit, causing fruit fall and fruit deformation.

Coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) It feed on fruits. Damaged young fruits show dark brown or grey indentations on the skin and normally drop. Bug feeding on mature fruit causes sunken lesions. The coconut bug is reddish brown, about 1.5 cm long. Eggs are laid scattered over the fruit, small twigs, flowers and blossom stems. The young bugs are light brown with long thick antenna.

Tip wilters (Anoplocnemis curvipes) They are large (about 2.5 cm long) bugs, and dark brown in colour. The hind legs of the male are enlarged. Both young and adult bugs feed on young flush, on the mid-vein of young leaves, or on flower stalks, causing wilting and death of new growth. Heliopeltis bugs, also known as mosquito bugs are about 7-10 mm long and have slender bodies and long legs and antenna. Adults and young bugs (nymphs) feed on fruit and young shoots. Feeding on fruit causes dark lesions with a brown dark centre. Young shoots die back, resulting in vigorous secondary branching. Bugs are difficult to control since they usually feed on a wide range of crops and are very mobile.

What to do:

|

| Helopeltis bugs (Helopeltis schoutedeni and H. anacardii) Helopeltis bugs, also known as mosquito bugs or mirid bugs are slender, delicate insects, about 7- 10 mm long with long legs and antennae, the antenna being nearly twice as long as the body. The females are red and the males brown to yellowish red. They lay eggs inserted into the soft tissue near the tips of flowering or vegetative shoots. Nymphs (immature bugs) are yellowish in colour. Both adults and nymphs feed on young leaves, young vegetative and flowering shoots, and developing fruits.

Attacked leaves are deformed and show angular lesions, particularly along the veins, which may drop off, so that the leaves appear as if attacked by biting insects. Feeding on the stalks of the tender shoots causes elongated green lesions, sometimes accompanied by exudation of gum. Severely damaged shoots die back due to the effect of bug saliva in combination with fungi, which enter the plant tissue through the feeding lesions and the subsequent development of numerous auxiliary buds causes a bunched terminal growth known as 'witches broom'. In case of serious infestations the trees may appear as if scorched by fire. Bug feeding on developing fruits causes brown sunken spots. The growth of trees is seriously retarded and fruit formation is reduced.

What to do:

|

| Mango leaf coating mite (Cisaberoptus kenyae) The mango leafcoating mite is tiny (about 0.2 mm), light coloured and cigar shaped. It cannot be seen with the naked eye. The mites leave in groups under a white coating on the upper leaf surface. The white coating can be easily rubbed off by hand. Leaves covered with the white coating tend to turn yellow and drop prematurely. In general, the coating has minimal effect on fruit yield.

What to do:

|

| Spider mites (Tetranychus spp.) They can damage maize from the seedling stage to maturity. The presence of small, faint yellow blotches on the lower leaves is an indication of spider mite injury. As the colonies of mites increase in size they cause the lower leaves to become dry. The mites then migrate to the upper leaves. In Africa several species of spider mites have been reported on maize (mainly Tetranychus spp. and Olygonichus spp.). In Kenya, they are occasionally found on maize, but usually they are not of economic importance.

What to do:

|

| Red banded thrips (Selenothrips rubrocinctus) The adult of the red banded thrips is reported as a pest of mangoes in Kenya (AIC, 2003). Adult thrips are dark brown, about 1 mm long. Immature thrips (nymphs) are yellow with a bright red band around the base of the abdomen. Nymphs and adults feed together, normally on the underside of the leaves. Attacked leaves become dark stained and rusty in appearance with small shiny black excreta present. Leaf edges are curled. Several other species of thrips are found on mango flowers. However, not all of them are pests. Their role varies according to the species. Some species are present in large numbers in mango flowers, but there is no evidence of damage or crop loss. Some thrips species are considered important pollinators. Other species of thrips attack the mango fruit. Thrips feeding on the fruit surface causes a rough, greyish white discolouration.

What to do:

|

| They are generally associated with old mango trees. They may damage branches and other parts by tunnelling the wood, but usually are not of economic importance. Sickly, injured plants are more likely to be damaged than healthy, vigorous plants.

What to do:

|

Information on Diseases

Biological methods of plant protection

The most usual diseases with mango trees are fungus and bacterial diseases. The first important preventative measure is make sure that the propagation segments are healthy. The scions that were raised in tree nurseries and whose origins are maybe unclear, should be carefully examined. They shall not have been treated with any synthetic or chemical agents.

Anthracnose, caused by the fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, is the most wide-spread disease among mangoes. The varieties vary in susceptibility. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides causes anthracnose on fruits, and drop of flowers on young branches. Anthracnose always appears as a result of scurvy (Elsinoe mangiferae). Fruits stricken with anthracnose can be plunged into a hot water bath (3- 5 min. at 55°C), in order to kill off the fungus. Preventative measures are nevertheless preferable, to preclude injuries and an infection with scurvy, because anthracnose can usually only take a hold on damaged fruits that are also affected by scurvy. A case of scurvy can usually be prevented by removing all dead plant material (branches, leaves and fruit). In exceptional cases, the fungus can be brought under control again with copper strays.

While anthracnose generally attacks ripe fruits (and blossoms), a bacterial infection from Erwinia sp. can also affect young fruit. The symptoms are very similar to the flecks caused to the leaves and fruit by anthracnose. The bacteria usually survive in the ground - a heavy rainfall will then splash the spores against the lower leaves and fruits. Covering the ground can therefore help to protect against this. Active life in the soil will also help to prevent an explosive growth of bacteria. Sites where it can rain inside the blossoms can also be a problem.

Young fruit and also blossoms can be damaged by powdery mildew (Oïdium mangiferae). This fungus grows during warm weather with high humidity. It attacks flowers and young fruits. A case of powdery mildew can dramatically affect the harvest. An open, well-ventilated orchard can prevent mildew. In acute cases, mildew can also be brought under control with sulphur. When carrying this out, there should be no wind blowing, and the leaves should still be moist with dew.

The leaf spot disease (Cercospora mangiferae) on mangoes is visible as dented spots on leaves and fruit. The same applies for this fungus, an open and quick-drying tree population is the best protection against infection. Fruit infected with Cercospora can no longer be sold, furthermore, both the leaf spot disease and scurvy prepare the way for anthracnose. In exceptional cases, the leaf spot disease can be brought under control copper sprays. For more information on Bordeaux Mixture click here

Examples of Mango Diseases and Organic Control Methods

| Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporiodes) The most serious and widespread fungus is anthracnose. Anthracnose initially appears as small black spots. On leaves, the spots can grow to form an irregular patch. On young fruit, pin-sized, brown or black, sunken spots develop. Sometimes, a "tear stain" pattern develops on fruit. It is an important problem after harvesting the fruit, especially during transport and storage, where fruit can develop round, blackish sunken spots. The fungus is spread by rain splash and survives from season to season on dead leaves and twigs. Rainy weather during blooming and early fruit set will favour the development of anthracnose.

What to do:

|

| Powdery mildew (Oidium mangifera) It appears as a white, powdery growth on leaves, flowers and young fruit. Infected leaves curl and flowers fail to open and drop from the tree without forming a fruit. The disease is spread by wind and can spread very rapidly. It is more prevalent in dry weather when humidity is high and nights are cool. The fungus survives from season to season in dormant buds. The flowering stage is the most critical stage for infection.

What to do:

|

| Bacterial black spot (Xanthomonas campestris pv. mangiferaeindicae) Bacterial black spot is rain related and is spread through rain splash within an orchard. Long-distance spread is by infected planting material. Important factors in infection are very small wounds that are easily caused by wind and wet weather. On leaves, spots are angular, dark, shiny in appearance and delimited by veins. Fruit spots start off as water soaked and then become raised and black. Later they crack open in the centre in form of a star. In wet weather, these spots exude gum. Fruit becomes more susceptible with age.

What to do:

|

| Malformation (Fusarium subglutinans) The fungus produces compounds that have hormonal effect on the plant. The fungus is easily spread by grafting and infected nursery trees. In the orchard the disease spreads slowly despite of masses of spores produced on the panicles. Symptoms consist of affected flowers taking on, to a greater or lesser extent, the appearance of a cauliflower head. The axes of the panicles are shorter and thicker than normal, branch more often, and a profusion of enlarged flowers is produced. The affected panicles retain their green colour, are sterile and produce no fruits. In the nursery, vegetative malformation can occur. Eriophid mites are believed to be vectors of the disease and their damage symptoms are similar to those caused by F. subglutinans. Symptoms consist of buds producing short shoots and small brittle leaves creating a compact "witches broom" appearance.

What to do:

|

| Stem-end rot (Dothiorella dominicana, Botryodiplodia theobromae, Phomopsis mangiferae) Symptoms consist of a dark-brown, firm decay starting at the stem-end of the fruit and developing rapidly to involve the whole fruit. The fungi survive on dead twigs and branches where they produce large numbers of spores. During wet weather, these spores are spread to adjacent fruits where infection occurs. The rot generally does not develop until the fruits begin to ripen. Chemical sprays are neither recommended nor necessary.

What to do:

|

Information Source Links

- AIC, Ministry of Agriculture, Nairobi Kenya (2003). Fruits and Vegetables Technical Handbook

- CAB International 2000 and 2005. Crop Protection Compendium. Wallingford, UK. www.cabi.org

- Griesbach, J. (1992). A guide to propagation and cultivation of fruit trees in Kenya. Schriftreihe der GTZ, No. 230. Eschborn, Germany. ISBN: 3-88085-482-3.

- Griesbach, J. (2003). Mango Growing in Kenya. World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). ISBN 92 9059 149 8. www.worldagroforestry.org

- Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops (ARC-LNR) (1998). The Cultivation of Mangoes. Compiled and edited by E.A. de Villiers. ISBN: 0-620-22320-0

- Mango organic cultivation guide, 2001, Naturland. Available online www.naturland.de

- Neuenschwander, P. (2003). Biological control of cassava and mango mealybugs. In Biological Control in IPM Systems in Africa. Neuenschwander, P., Borgemeister, C and Langewald. J. (Editors). CABI Publishing in association with the ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). pp. 45-59. ISBN: 0-85199-639-6.

- Nutrition Data. www.nutritiondata.com.

- OISAT (Online Information Service for Non-Chemical Pest Management in the Tropics). www.oisat.org

- Tandon PL, Lal B. (1978). The mango coccid Rastrococcus iceryoides Green (Homoptera: Coccidae) and its natural enemies. Current Science, 47(13):467-468.

- Varela, A.M., Seif, A., Nyambo, B. (2006). A Guide to IPM in Mango Production in Kenya. ICIPE. Modern Lithographic Ltd., Nairobi, Kenya. www.icipe.org

Contact Information

- Corner Shop, Nairobi: cornershop@africaonline.co.ke, +254 (0) 0716 905 486, (20) 2712268/9

- Food Crop research Institute, Muguga Sub Centre (fcri@kalro.org +254 (20) 3509161)

- Green Dreams: info@organic.co.ke +254 (0) 724 781 971/ 0722 562 717

- Horticultural Crops Directorate: info@agricultureauthority.go.ke, +254 20 2536869, 0722 200 556

- Industrial Crop Research Institute, Mtwapa (icri@kalro.org; +254 (20) 2024751)

- Kalimoni Greens: www.kalimonigreens.com , +254 (0) 708 278 273

- Karen Provision Stores, Nairobi: kps@nbi.ispkenya.com +254 20 882 252, 0736 371 437

- Muthaiga Green Grocers, Nairobi

- Nakumatt Supermarket: info@nakumatt.net, +254 (0) 733 632 130, 0722 204 931, (20) 3599991-4

- Horticulture Research Institute, Thika: director.hri@kalro.org. +254 (20) 2055038

- Uchumi Supermarket: info@uchumi.com +254 20 8020081 - 5, 0733 410 028,

- Zuchinni Green Grocers, Nairobi: +254 (20) 2215067