Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Papaya in Africa. Updated on 8 July 2019. Source FAOSTAT.

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

Papaya is a widely cultivated fruit tree in the tropics and subtropics. It is a popular fruit in Kenya. Ripe papaya is a favourite breakfast and dessert fruit that is available year-round. It can be used to make fruit salads, refreshing drinks, jam, jelly, marmalade, candies and crystallised fruits. Green fruits are pickled or cooked as a vegetable. Young leaves are sometimes eaten. In some countries, seeds are used as vermifuge and to induce abortion (abortifacient).

Carpaine, an alkaloid present in papaya, can be used as a heart depressant, amoebicide and diuretic. In some countries papaya is grown in sizeable plantations for the extraction of papain, an enzyme present in the latex, collected mainly from the green fruit. Papain has varied uses in the beverage, food and pharmaceutical industries: in chill-proofing beer, tenderizing meat, drug preparations for digestive ailments and treatment of gangrenous wounds. It is also used in treating hides, degumming silk and softening wool.

There are 3 groups of papayas distinguished on the basis of their flowers: Female (pistillate), male (staminate) and hermaphrodite (bear both male and female flowers). These groups are only distinguishable at flowering stage. Fruits from female flowered trees are usually sweeter and of more round shape than fruits from hermaphrodite trees.

Nutritive Value per 100 g of edible Portion

| Raw or Cooked Papaya | Food Energy (Calories / %Daily Value*) |

Carbohydrates (g / %DV) |

Fat (g / %DV) |

Protein (g / %DV) |

Calcium (g / %DV) |

Phosphorus (mg / %DV) |

Iron (mg / %DV) |

Potassium (mg / %DV) |

Vitamin A (I.U) |

Vitamin C (I.U) |

Vitamin B 6 (I.U) |

Vitamin B 12 (I.U) |

Thiamine (mg / %DV) |

Riboflavin (mg / %DV) |

Ash (g / %DV) |

| Papaya raw | 39.0 / 2% | 9.8 / 3% | 0.1 / 0% | 0.6 / 1% | 24.0 / 2% | 5.0 / 1% | 0.1 / 1% | 257 / 7% | 1094 IU / 22% | 61.8 / 103% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.6 |

*Percent Daily Values (DV) are based on a 2000 calorie diet. Your daily values may be higher or lower, depending on your calorie needs.

Climate conditions, soil and water management

Papaya thrives in warm areas with adequate rainfall and a temperature range of 21-33°C. Its altitude range is similar to that of the banana, from sea level to elevations at which frosts occur (often around 1600 m). However they grow best in areas below 1000 m. The quality and yield are low at higher altitudes. Frost can kill the plant, and cool and overcast weather delays fruit ripening and depresses fruit quality. Fruit tastes much better when grown during a warm sunny season. Evenly distributed annual rainfall of 1200 mm is sufficient if water conservation practices are employed. Plantations should be in sheltered locations or surrounded by windbreaks; strong winds are detrimental, particularly on sandy soils, as they cannot make up for large transpiration losses.

Papaya grows best in light, well-drained soils rich in organic matter with soil pH of 6.0-6.5. It can tolerate any kind of soil provided it is well-drained and not too dry. The roots are very sensitive to waterlogging and even short periods of flooding can kill the plants.

Propagation and planting

Papaya is propagated by seed. To reproduce the desired characteristics it is best to get seeds through controlled pollination. The fleshy outer layer of the seed coat (sarcotesta) enveloping the seed is removed because it inhibits germination. This is achieved by rubbing the seed together against a fine-meshed screen under running water. Thoroughly dried seeds stored in air-tight containers remain viable for several years. Seeds are sown in small containers (tin cans, plastic bags or paper cups) at the rate of 3-4 seeds per container. Use of sterilised soil minimises losses resulting from nematodes and damping-off fungi. Germination takes 2-3 weeks. Another practice is to sow the seeds in sterilised nursery beds and to prick out at the 2-3-leaf stage, transferring 3-4 seedlings to each container. Seedlings are transplanted about 2 months after sowing when they reach the 3-4-leaf stage or 20 cm height, preferably at the onset of the rainy season. During transplanting, take care not to disturb the roots. Older seedlings recover poorly after planting out.

Papaya needs adequate drainage and is often planted on mounds or ridges. Transplants must be watered regularly until they are established. Field spacings are in the order of 3 x 2 m to 2.50 x 1.60 m, giving densities of 1667 and 2500 plants/ha respectively. The same densities are obtained by planting in double rows spaced (3.25+1.75) x 2.40 m or (2.50+1.50) x 2 m. Thinning to one female or one hermaphrodite plant per hill is done when the plants reach the flowering stage. In the absence of hermaphrodite plants, 1 male plant per 25 - 100 female plants is retained as pollinator.

Papaya plants grown from seed produce fruits of different shapes, sizes, colour and even taste. Vegetative propagation of papaya provides a solution to most of these problems. The clone is selected for higher productivity and good quality fruits besides agronomic qualities such as dwarfness for easy harvesting and good resistance to diseases. Propagation of papaya using tissue culture is fast gaining popularity, mainly because tissue culture has numerous advantages over other conventional methods of propagation. Tissue culture facilitates rapid production of disease free plants. In Kenya such plants are available from Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), Thika as well as several private companies.

Planting holes of 60 x 60 cm and at least 50 cm deep are prepared with 1 bucket of compost and a handful of rock phosphate is mixed in with the dug out soil and returned around the plant. Firm the soil and water liberally and add mulch around the young plant.

Major varieties include:

- Honey Dew'. This is an Indian variety of medium height that produces oval juicy medium size fruit.

- 'Kiru'. Is a Tanzanian variety that produces large fruits. It is a high yielder of papain.

- 'Mountain'. Originally the name for a variety grown at high altitudes with very small fruits only suitable for jam and preserves. Now the name is also used for a medium size variety with good fresh consumption qualities such as firm sweet tasting yellow flesh.

- 'Solo'. It is a Hawaiian variety that produces small round very sweet fruits with uniform size and shape. It is hermaphroditic.'

- Sunrise Solo'. Hawaiin variety that produces smooth pear shaped fruit of high quality, weighing 400 to 650 g. The flesh is reddish orange. This variety is high yielding.

- 'Sunset': Hawaiian variety with red flesh and having same characteristics as 'Solo'

- 'Waimanalo'. Hawaiian variety that produces smooth, shiny round fruits with short neck and is of high quality. The flesh is orange yellow, thick, sweet and firm.

Most of commercial varieties grown in Kenya are derived from Hawaii. A few are from India and some known as 'Mountain varieties' whose origin / source is a rather not explained. None of these have been reported to haveresistance to Phytophthora palmivora. However, information available claims that Hawaiian lines such as 'Waimanalo 23', 'Waimanalo 24' and 'Line 40' exhibit resistance to P. palmivora.

Another serious disease problem with papaya is papaya ring spot virus. However, according to a recent report by PIP COLEACP (www.coleacp.org/en), there are no commercial papaya varieties, except for transgenic, which are tolerant or resistant to papaya ring spot virus or bunchy top virus.

Intercropping

Papaya grows best when planted in full sunlight. However, it can be planted as an intercrop under coconut, or as a cash crop between young fruit trees such as mango or citrus. Low growing annual crops such as capsicums, beans, onions and cabbages are suitable good intercrops.

Husbandry

Clean cultivation is standard practice and weed control, particularly around the small plants, is very important. If weeds are only slashed - resulting in a grassy weed cover - papaya plants suffer severe competition. Experimental work shows a very good response to mulching. Irrigation is needed to minimise the abortion of flowers and maintain growth during the dry season. Watering once a week is recommended. Papaya is a fast-growing crop that requires a lot of nutrients. The use of manure and mulchsteadies the release of nutrients. Calcium deficiency depresses growth and fruit set and enhances fruit drop; liming (to a pH of about 6) is the remedy.

Harvesting

The stage of physiological development at the time of harvest determines the flavour and taste of the ripened fruit. The appearance of traces of yellow colour on the fruit indicates that it is ready for harvesting. Fruits harvested early have longer post harvest life, but give abnormal taste and flavour. The fruits also tend to shrivel and suffer chilling injuries when refrigerated. The fruit is twisted until the stalk snaps off or cut with a sharp knife. Yields per tree vary from 30 to 150 fruits annually, giving 35 to 50 tons of fruit per ha per year. A papaya plantation can be productive for over 10 years but the economical period is only the first 3 to 4 years. It is therefore advisable to renew the plantation every 4 years.

For papain production, latex is collected by tapping the green unripe fruit. Four longitudinal incisions, skin-deep and 2 to 3 cm apart are made with a sharp, non-corrosive rod (glass, plastic or horn). Latex is collected in a clean glass or porcelain container and dried, or a canvas covered tray fixed onto the trunk of the tree. The latex is later scraped off the canvas with a wooden scraper and dried. Fruits may be tapped once a week, until they show signs of ripening. The operation is best done early in the morning (before 10:00) because the latex flows slowly in hot weather. Tapping results in ugly scars on the fruit, although quality is unaffected. Tapped fruit can be processed or used as animal feed. The papain producing trees are productive for 2 to 3 years, with the first 2 years being the most productive. If kept longer production is uneconomical.

| Two species of fruit flies have been recorded from papaya in East Africa, namely Bactrocera invadens and Ceratitis rosa (personal communication S. Ekesi, AFFI, icipe). The flies usually deposit their eggs in ripe fruit. Some fruit flies lay eggs on green pawpaw, but most of the eggs die due to the latex secreted when fruits are punctured by females while laying eggs. Developing larvae cause rotting of ripening fruits. Fruit flies are a major concern of papaya-importing countries.

What to do:

|

| Several species of mites damage papaya (personal communication, M. Knapp, ICIPE):

The spider mites suck the plant sap, leading to poor plant growth and blemish on the fruit. Infested leaves show yellow patches on the upper surface, particularly between main veins and midrib. Feeding by mites causes scarring and discolouration of fruit, and reduced fruit size affecting its market value. Infestations usually begin on the older leaves and the spreads to the younger growth. Serious infestations occur during long dry periods. Broad mites attack mainly the terminal buds; they feed on the young leaves as they emerge from the growing point. Affected leaves are thick and brittle, with down curled edges. Severe infestations inhibit new stem growth, with consequent reduction in fruit production. What to do:

|

| False spider mite (Brevipalpus phoenicis) The adults are about 0.1 mm. It usually feeds on the trunk below the level where the bottom whorl of leaves is attached. The mites move upward on the trunk and outward onto the leaves and fruit as the population increases, leaving a large, conspicuous, damaged area behind them. The affected area becomes raised and blister-like. Later the affected tissue dries up, dies and becomes discoloured, forming a large and continuous callous area, light brown and scaly and/or scabby. Damage by feeding on young papaya fruits is manifested by sunken areas. Sometimes feeding by the mite causes a copious outflow of a milky white liquid that mars the appearance of the fruits. Under heavy mite infestations, the papaya stem, which normally remains green for a long time, becomes brownish and corky in appearance, and has a spindly growth (Martin Kessing and Mau, 1992; CABI Compendium, 2000).

What to do:

|

| Broad mite (Polyphagotarsonemus latus) Broad mites are tiny (0.1-0.2 mm long) cannot be seen with the naked eye, and are even difficult to detect with a hand lens. In addition, they often disappear before the damage is noticed. Therefore an attack by broad mites is usually detected by the symptoms of damage. Broad mite attacks mainly the growing point and the underside of young leaves causing hardening and distortion. Severe infestations inhibit new stem growth, with consequent reduction in fruit production. Broad mite damage may be confused with injury caused by some herbicides because in both cases the leaves become claw-like with prominent veins. Grey or bronze scar tissue between the veins on the underside of the leaves distinguishes mite from herbicide damage. For early detection of damage inspect the growing point of the tree regularly. This is important to allow control the pest before serious distortion of terminal growth occurs.

What to do:

|

| Cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii) and green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) These are the most important aphids in papaya growing. These insects suck sap from young leaves and flowers and may weaken the plants. However, this type of damage is usually of little importance. Their importance as pests is mainly due to their ability to transmit virus diseases, for instance the papaya ring spot virus and the papaya mosaic virus. Few aphids are enough to transmit mosaic virus. These aphids are also found on other crops such as cucurbits, potatoes and tobacco.

What to do:

|

| Systates weevil (Systates spp.) This is a very common weevil in East Africa. It attacks many crops and ornamental plants. The adult is a black weevil, about 12 mm long with a swollen, rounded abdomen, and long, thin, elbowed antenna. It is active at night, feeding on the edges of leaves producing a characteristic indentations. During the day it hides in the mulch, at the base of plants or in loose soil near plants. They feed on a wide range of crops and wild plants. They can be a problem to young papaya plants when present in large numbers. What to do:

|

| Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne incognita) Feeding root-knot nematodes cause root swellings or root galls, resulting in yellowing and premature abscission of the leaves. Infestation by nematodes reduces growth and yield. In nurseries, severely infested seedlings wilt and die.

What to do:

|

| Mealybugs are small, flat, soft bodied insects covered with a distinctive segmentation. Their body is covered with a white woolly secretion. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruits. Seriously attacked leaves turn yellow and eventually dry. This can lead to shedding of leaves, inflorescences, and young fruit. Mealybugs excrete honeydew on which sooty mould developed. Heavy coating with honeydew blackens the leaves, branches and fruit. This reduces photosynthesis, can cause leaf drop and affect the market value of the fruit.

A wide range of natural enemies attacks mealybugs. The most important are ladybird beetles, hover flies, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. These natural enemies usually control mealybugs. However, mealybugs can cause economic damage to mango when natural enemies are disturbed (for instance by ants feeding on honeydew produced by mealybugs or other insects) or killed by broad-spectrum pesticides, or when mealybugs are introduced to new areas, where there are no efficient natural enemies.

The latter is the case of two serious mealybug pests on mangoes in Africa: Rastrococcus invadens in West and Central Africa and Rastrococcus iceryoides in East Africa. These mealybugs, of Asian origin, were introduced into Africa, where they developed into serious pests since the natural enemies present were not able to control them. They cause shedding of leaves, inflorescences and young fruits. In addition, sooty moulds growing on honeydews excreted by the insects render the fruits unmarketable and the trees unsuitable for shading. They cause direct damage to fruits leading to 40 to 80% losses depending on locality, variety and season. Rastrococcus invadens was brought under control in West and Central Africa by two parasitic wasps (Gyranusoidea tebygi and Anagyrus mangicola) introduced from India (Neuenschwander, 2003).

Rastrococcus iceryoides is a major pest of mango in East Africa, mainly Tanzania and coastal Kenya. Although several natural enemies are known to attack this mealybug in its aboriginal home of southern Asia (Tandon and Lal, 1978; CABI, 2000), none have been introduced so far into Africa (ICIPE). Insecticides do not generally provide adequate control of mealybugs owing to their wax coating. What to do:

|

| Several species of whiteflies are found on cassava in Africa. Feeding causes direct damage, which may cause considerable reduction in root yield if prolonged feeding occurs. Some whiteflies cause major damage to cassava as vectors of cassava viruses. The spiralling whitefly (Aleurodicus dispersus) was reported as a new pest of cassava in West Africa in the early 90s. The adults and nymphs of this whitefly occur in large numbers on the lower surfaces of leaves covered with large amount of white waxy material. Females lay eggs on the lower leaf surface in spiral patterns (like fingerprints) of white material secreted by the female. This whitefly sucks sap from cassava leaves. It excretes large amounts of honeydew, which supports the growth of black sooty mould on the plant, causing premature fall of older leaves.

The tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) transmits the African cassava mosaic virus, one of the most important factors limiting production in Africa. The adults and nymphs of the tobacco whitefly occur on the lower surface of young leaves. They are not covered with white material. The nymphs appear as pale yellow oval specks to the naked eye.

What to do:

|

| These are caused by the soil-borne fungi Phytophthora parasitica, P. palmivora and Pythium aphanidermatum. Phytophthora and Pythium also occur in the orchard, causing root rot. Stem and fruit rots are produced on papaya. Infected young fruits develop water-soaked lesions that exude milky latex. These fruits may eventually shrivel and fall off the trunk. Infected trees show yellowing of leaves, which later collapse and hang limply around the trunk before falling. Small roots are generally absent and large ones show a soft, wet decay extending towards the trunk. At that stage, the lateral roots and taproots are entirely destroyed and a foul odour often emanates from diseased trees. Stem cankers, which develop most frequently in the top of the stem where the fruit is borne, induce fruit and leaf fall. These fungi may also cause trunk rot of mature trees. Infected trees eventually die. Plants are susceptible at all ages but roots of young seedlings are most susceptible. What to do:

|

| Several fungal pathogens are involved in fruit decay. They include Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Glomorella cingulata), Alternaria tenuis, Phomopsis caricae-papayae and Ascochyta caricae. Symptoms first appear as brown, superficial discolourations of the skin. These develop into circular, more or less sunken spots and tend to occur in a group on the outer exposed side of the fruit and often join to form a large rotted area extending deep into the flesh. The fungi causing ripe fruit rots live on dying leaf stalks and produce spores, which spread to the fruit particularly during wet weather. Several of these fungi, especially, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, may infect green fruit and remain dormant in the tissues until ripening when they develop rapidly. They constitute a big post-harvest problem especially during transport and storage.

What to do:

|

| Powdery mildew (Oidium caricae; Sphaerotheca humili) Young crown leaves show light green patches covered by a white powdery growth. Fruits develop circular, white patches on the surface. As the fruits develop, the white mould disappears leaving grey-scarred areas. The disease is particularly severe on immature tissue. The white mildew produced on leaves and fruits, contains large numbers of spores, which are spread to adjacent trees by wind and rain.

What to do:

|

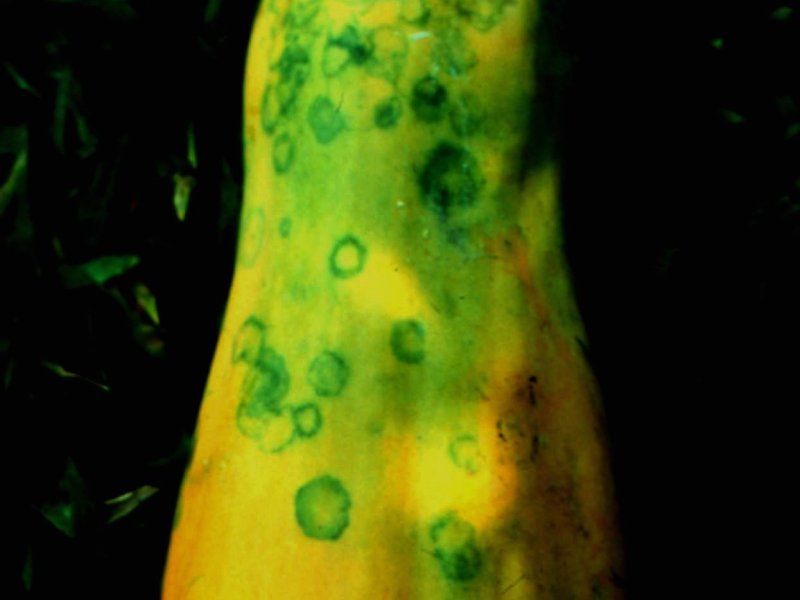

| It is a devastating virus disease. In Africa, it occurs in Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda. Initially, the disease appears as oil streaks on stems and petioles and as it progresses, mottling of leaves becomes evident. Severely infected plants do not flower and die young. Infected fruits develop characteristic line patterns, which form rings and remain green when fruits ripen. The virus is spread by aphids and it is also mechanically transmitted.

What to do:

|

Information Source Links

- AIC (2003). Fruits and Vegetables Technical handbook. Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock

- Beije, C., Kanyagia, S. T., Muriuki, S. J., Otieno, E. A., Seif, A. A., Whittle. A. M. (1984). Horticultural Crops Protection Handbook. National Horticultural Research Station, Thika, Kenya.

- CABI (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 Edition. © CAB International Publishing. www.cabi.org

- De Villiers, E. A. (1999). The Cultivation of Papaya. Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops. Published ARC.LNR. South Africa.

- De Villiers, E. A., Willers, P. (1995). Papaya pests. In Papaya. Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops. Published by the ARC. South Africa.

- EcoPort: Information on Ethnobotany: www.ecoport.org

- GTZ-Integration of Tree Crops into Farming Systems Project (2000). Tree Crop Propagation and Management - A Farmer Trainer Training Manual. BMZ/GTZ/ UNEP/ Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Kenya.

- Griesbach, J. (1992). A guide to propagation and cultivation of fruit trees in Kenya. GTZ. Germany. Schriftenreihe der GTZ, No. 230. ISBN 3-88085-482-3.

- Horticultural crops protection handbook. National Horticultural Research Station, Thika. Kenya 170 pp.

- Kessing, J.L.M. and Mau, R.E.L. (1992). Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes), Red and Black Flat Mite. Crop Knowledge Master. Department of Entomology. Honolulu, Hawaii. www.extento.hawaii.edu

- Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

- PIP Technical Itinerary Papaya. www.coleacp.org/en

- Papaya. Export Manual. Tropical fruits and Vegetables. Protrade, GTZ

- Papaya organic cultivayion guideline, 2000, Naturland. Available also online www.naturland.de/en/

- Pests of papaya. Broad mite in papaya. Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries. Queensland. David Astridge,. Last updated: December 2003. www2.dpi.qld.gov.au